Cheat Sheet of NLP Practitioner

I am actively maintaining this blog post, gathering NLP papers around large language models, information extraction, structured data-related downstream applications, {retrieval, tool}-augmented language models, prompting techniques and beyond.

Table of Contents

- 1. Knowledge Retrieval - Augmented Language Model

- Retrieval Meets Long Context Large Language Models (Xu, arxiv 2023)

- Meta-training with Demonstration Retrieval for Efficient Few-shot Learning (Mueller, Finding ACL 2023)

- GLIMMER: generalized late-interaction memory reranker (de Jong, arxiv 2023)

- Pre-computed memory or on-the-fly encoding? A hybrid approach to retrieval augmentation makes the most of your compute (de Jong, ICML 2023)

- How Does Generative Retrieval Scale to Millions of Passages? (Pradeep∗ et al., GenIR@SIGIR 2023)

- Recitation-Augmented Language Models (Sun et al., ICLR 2023)

- REPLUG: Retrieval-Augmented Black-Box Language Models (Shi et al., arxiv 2023)

- Rethinking with Retrieval: Faithful Large Language Model Inference (He et al., arxiv 2023)

- Interleaving Retrieval with Chain-of-Thought Reasoning for Knowledge-Intensive Multi-Step Questions (Trivedi et al., ACL 2023)

- Transformer Memory as a Differentiable Search Index (Tay et al., Neurips 2022)

- Autoregressive Search Engines: Generating Substrings as Document Identifiers (Bevilacqua et al., Neurips 2022)

- Atlas: Few-shot Learning with Retrieval Augmented Language Models (Izacard et al., arxiv 2022)

- EIDER: Empowering Document-level Relation Extraction with Efficient Evidence Extraction and Inference-stage Fusion (Xie et al., ACL Findings 2022)

- Don’t Prompt, Search! Mining-based Zero-Shot Learning with Language Models (van de Kar et al., EMNLP 2022)

- SKILL: Structured Knowledge Infusion for Large Language Models (Moiseev et al., NAACL 2022)

- Leveraging Passage Retrieval with Generative Models for Open Domain Question Answering (Izacard et al., EACL 2021)

- REALM: Retrieval-Augmented Language Model Pre-Training (Guu et al., ICML 2020)

- Generalization through Memorization: Nearest Neighbor Language Models (Khandelwal et al., ICLR 2020):

- 2. Information Extraction

- How to Unleash the Power of Large Language Models for Few-shot Relation Extraction? (Xu et al., SustaiNLP@ACL 2023)

- GPT-RE: In-context Learning for Relation Extraction using Large Language Models (Wan et al., arxiv 2023)

- Universal Information Extraction as Unified Semantic Matching (Lou et al., AAAI 2023)

- StructGPT: A General Framework for Large Language Model to Reason over Structured Data (Jiang et al., arxiv 2023)

- GPT4Graph: Can Large Language Models Understand Graph Structured Data? An Empirical Evaluation and Benchmarking (Guo et al., arxiv 2023)

- NEUROSTRUCTURAL DECODING: Neural Text Generation with Structural Constraints (Bastan et al., ACL 2023)

- Retrieval-Enhanced Generative Model for Large-Scale Knowledge Graph Completion (Yu et al., SIGIR 2023)

- Knowledge Base Completion for Long-Tail Entities (Chen et al., arxiv 2023)

- InstructUIE: Multi-task Instruction Tuning for Unified Information Extraction (Wang et al., arxiv 2023)

- Unifying Molecular and Textual Representations via Multi-task Language Modelling (Christofidellis et al., ICML 2023)

- Triggering Multi-Hop Reasoning for Question Answering in Language Models using Soft Prompts and Random Walks (Misra et al., Findings ACL 2023)

- Flexible Grammar-Based Constrained Decoding for Language Models (Geng et al., arxiv 2023)

- Methods for Measuring, Updating, and Visualizing Factual Beliefs in Language Models (Hase et al., EACL 2023)

- Can LMs Learn New Entities from Descriptions? Challenges in Propagating Injected Knowledge (Onoe et al., ACL 2023)

- DEMONSTRATE–SEARCH–PREDICT: Composing retrieval and language models for knowledge-intensive NLP (Khattab et al., arxiv 2023)

- CODEIE: Large Code Generation Models are Better Few-Shot Information Extractors (Li et al., ACL 2023)

- Evaluating Language Models for Knowledge Base Completion (Veseli et al., ESWC 2023)

- Exploiting Asymmetry for Synthetic Training Data Generation: SynthIE and the Case of Information Extraction (Josifoski et al., arxiv 2023)

- Large Language Model Is Not a Good Few-shot Information Extractor, but a Good Reranker for Hard Samples! (Ma et al., arxiv 2023)

- Understanding Fine-tuning for Factual Knowledge Extraction from Language Models (Kazemi et al., submitted to JMLR)

- Crawling The Internal Knowledge-Base of Language Models (Cohen et al., TBD)

- GREASELM: Graph Reasoning Enhanced Language Models for Question Answering (Zhang et al., ICLR 2022)

- Entity Cloze By Date: What LMs Know About Unseen Entities (Onoe et al., Finding NAACL 2022)

- Large Language Models Struggle to Learn Long-Tail Knowledge (Kandpal et al., arxiv 2022)

- Unified Structure Generation for Universal Information Extraction (Lu et al., ACL 2022)

- GenIE: Generative Information Extraction (Josifoski et al., NAACL 2022)

- EIDER: Empowering Document-level Relation Extraction with Efficient Evidence Extraction and Inference-stage Fusion (Xie et al., ACL Findings 2022)

- KnowPrompt: Knowledge-aware Prompt-tuning with Synergistic Optimization for Relation Extraction (Chen et al., The WebConf 2022)

- Rewire-then-Probe: A Contrastive Recipe for Probing Biomedical Knowledge of Pre-trained Language Models (Meng et al., ACL 2022)

- Do Pre-trained Models Benefit Knowledge Graph Completion? A Reliable Evaluation and a Reasonable Approach (Lv et al., ACL-Findings 2022)

- SimKGC: Simple Contrastive Knowledge Graph Completion with Pre-trained Language Models (Wang et al. ACL 2022)

- Task-specific Pre-training and Prompt Decomposition for Knowledge Graph Population with Language Models (Li et al., LM-KBC@ISWC 2022 Challenge)

- GENRE: Autoregressive Entity Retrieval (De Cao et al., ICLR 2021).

- Structured Prediction as Translation Between Augmented Natural Languages (Paolini et al., ICLR 2021)

- How Can We Know What Language Models Know? (Jiang et al., TACL 2020)

- 3. Prompting Methods

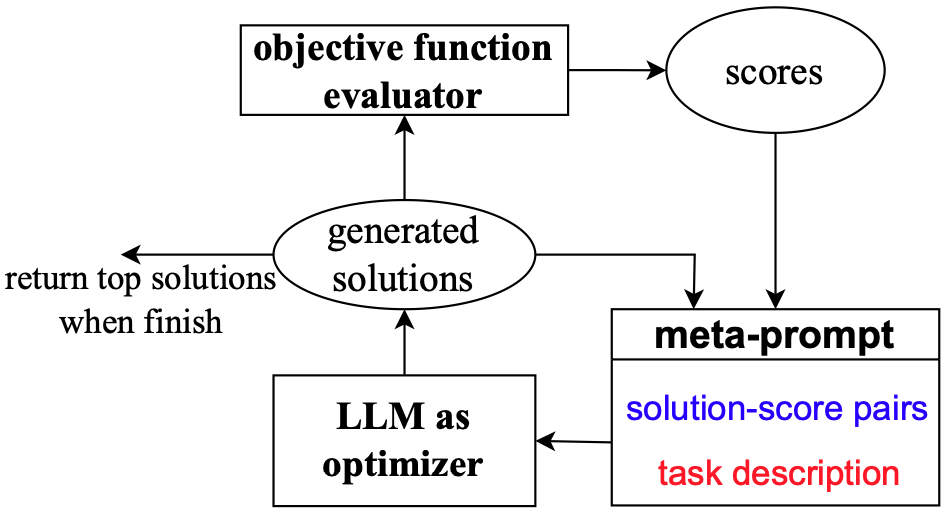

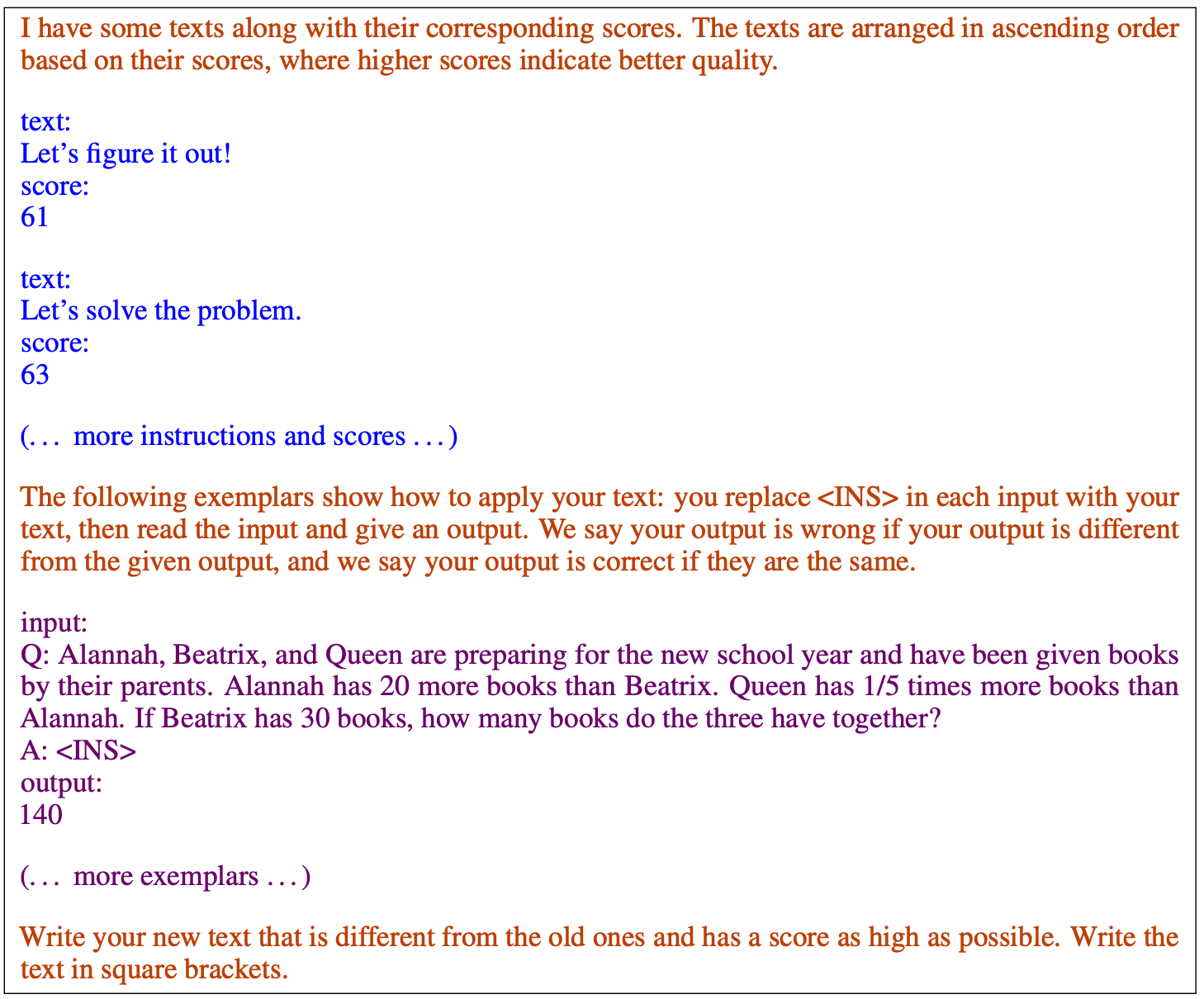

- Large Language Models as Optimizers (Yang, arxiv 2023)

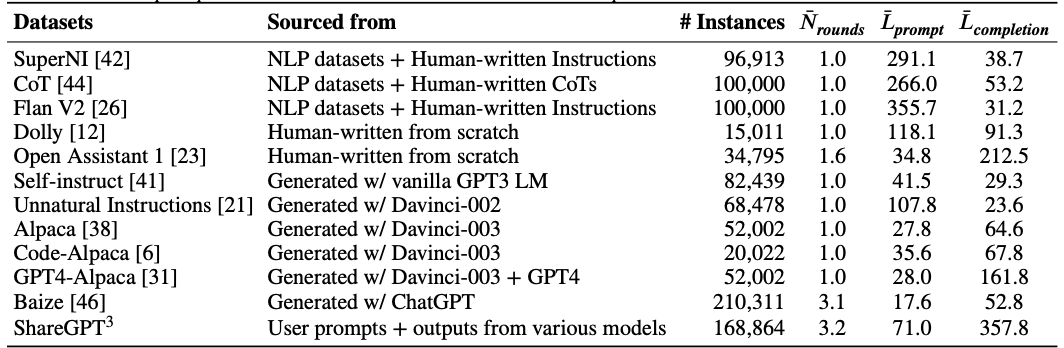

- How Far Can Camels Go? Exploring the State of Instruction Tuning on Open Resources (Wang et al., arxiv 2023) + The Flan Collection: Designing Data and Methods for Effective Instruction Tuning (Longpre et al., ICML 2023)

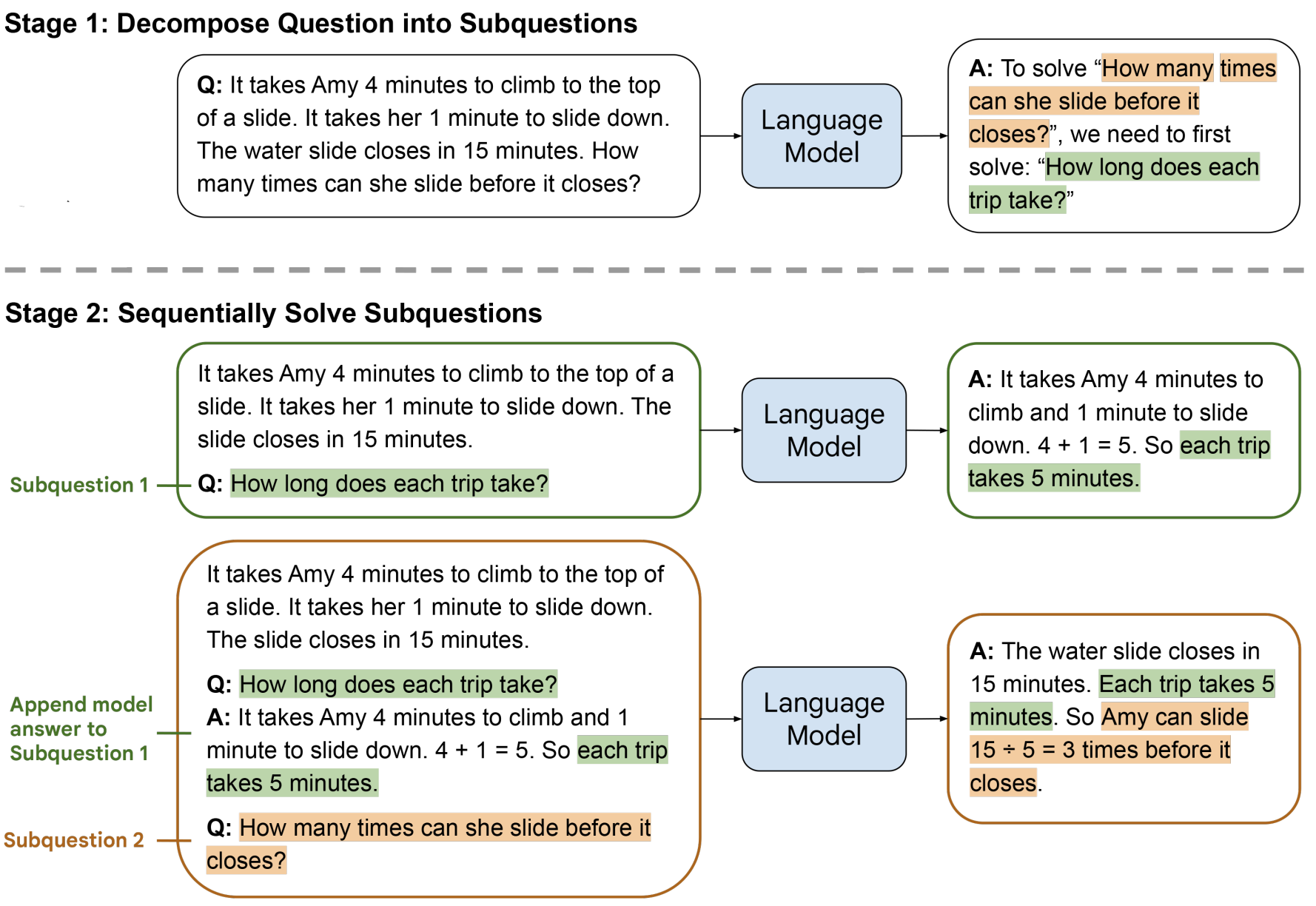

- Least-to-Most Prompting Enables Complex Reasoning in Large Language Models (Zhou et al., ICLR 2023)

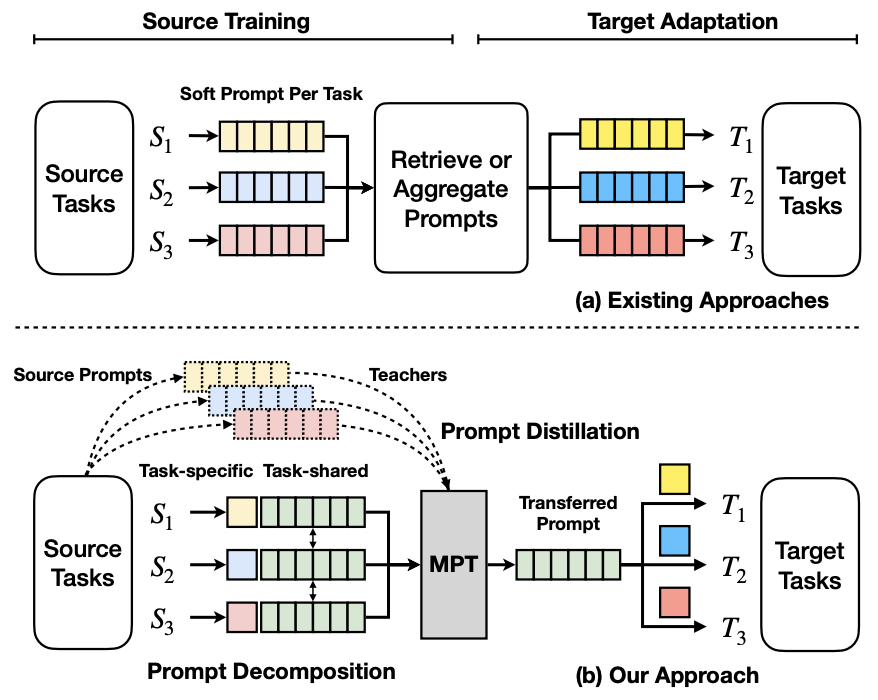

- Multitask Prompt Tuning enables Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning (Wang et al., ICLR 2023)

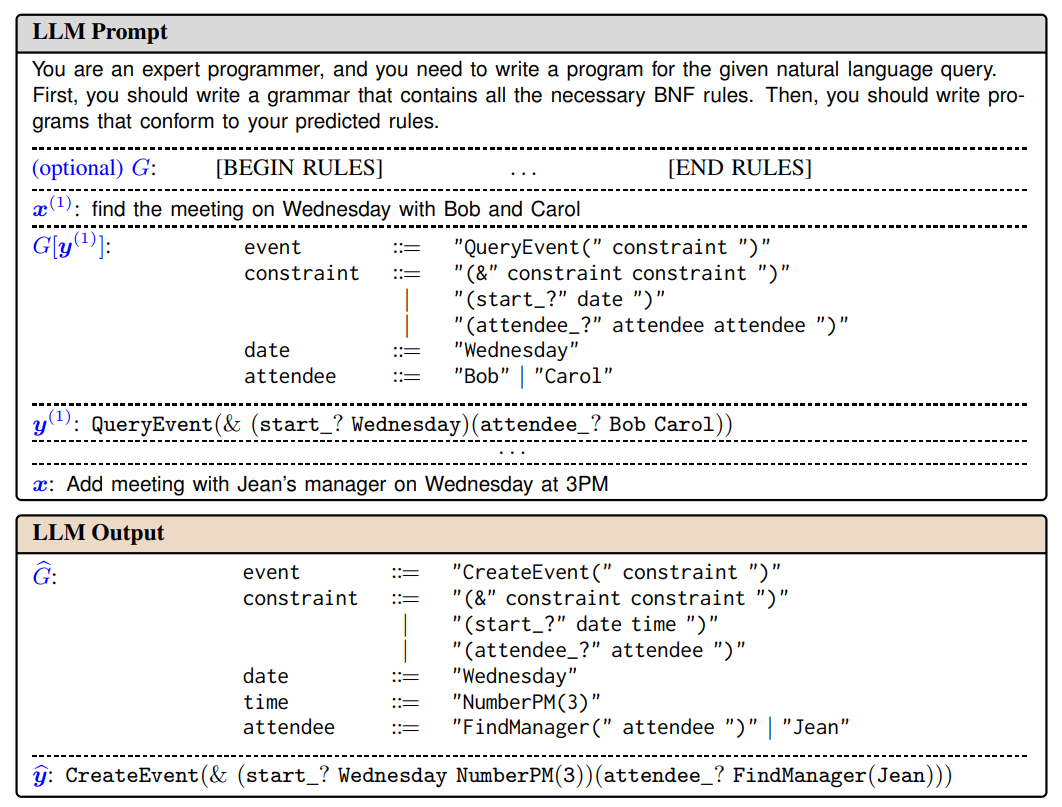

- Grammar Prompting for Domain-Specific Language Generation with Large Language Models (Wang et al., arxiv 2023)

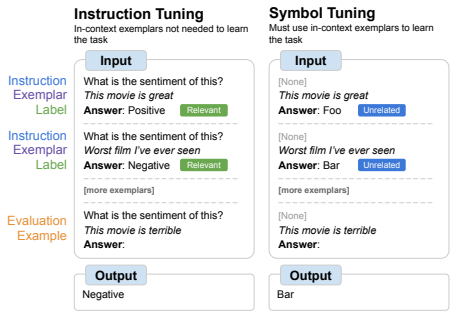

- Symbol Tuning Improves In-Context Learning In Language Models (Wei et al., arxiv 2023)

- Selective Annotation Makes Language Models Better Few-Shot Learners (Su et al., ICLR 2023)

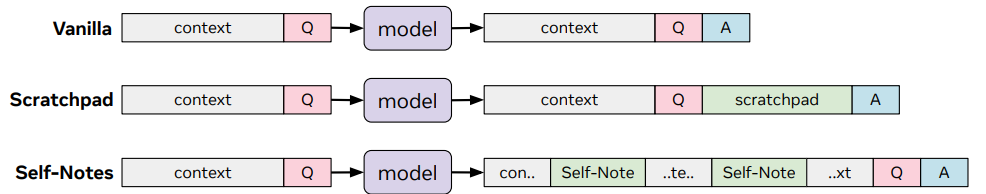

- Learning to Reason and Memorize with Self-Notes (Lanchantin et al., arxiv 2023)

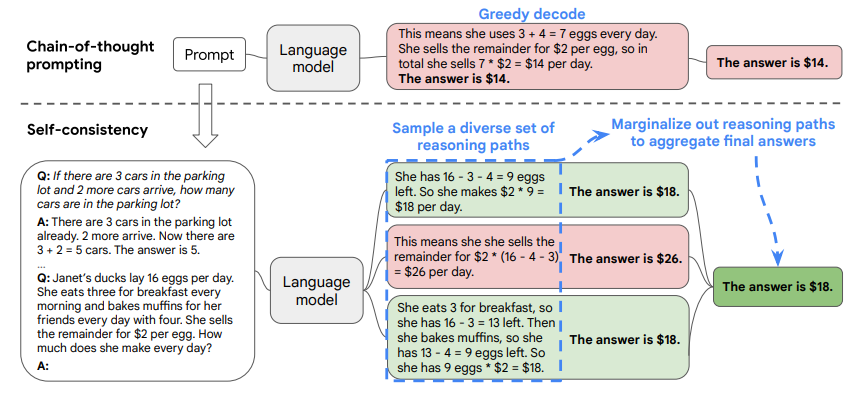

- Self-Consistency improves Chain Of Thought Reasoning in Language Models (Wang et al., ICLR 2023)

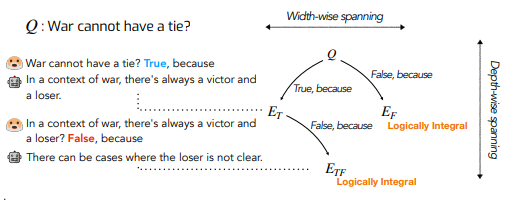

- Maieutic Prompting: Logically Consistent Reasoning with Recursive Explanations (Jung et al., EMNLP 2022):

- MetaICL: Learning to Learn In Context (Min et al., NAACL 2022)

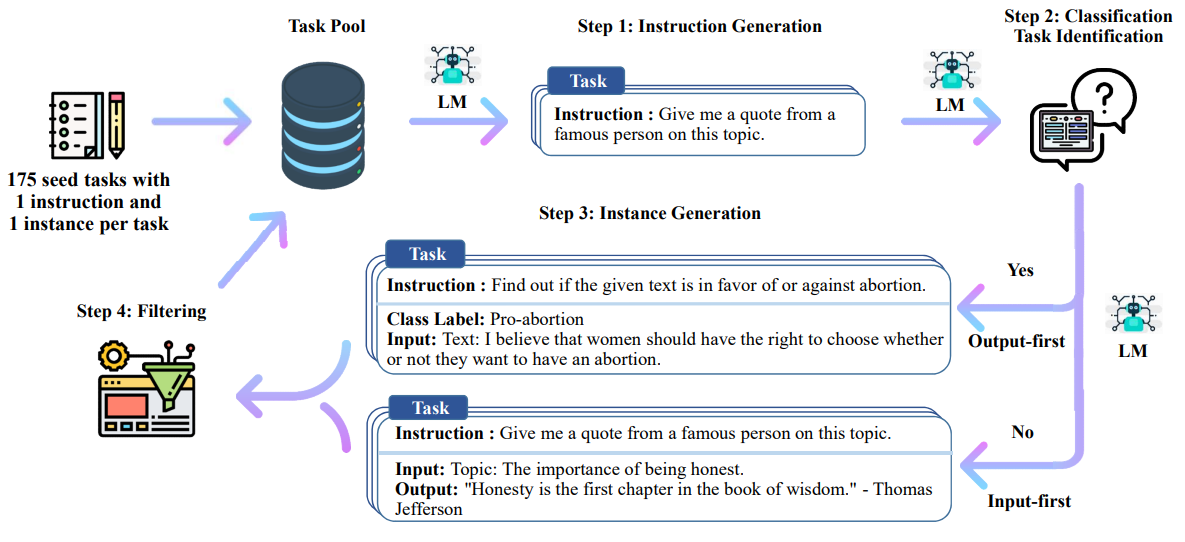

- Self-Instruct: Aligning LM with Self Generated Instructions (Wang et al., arxiv 2022)

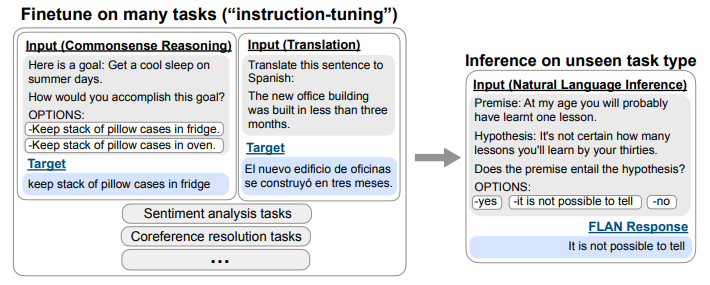

- Finetuned Language Models are Zero-Shot Learners (Wei et al., ICLR 2022)

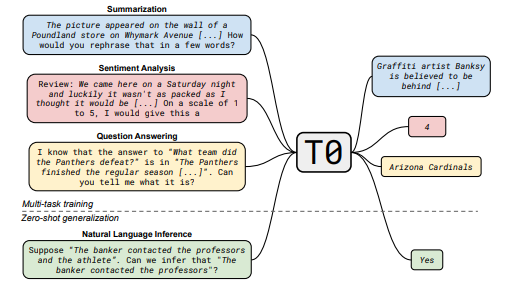

- Multitask Prompted Training Enables Zero-Shot Task Generalization (Sanh et al., ICLR 2022)

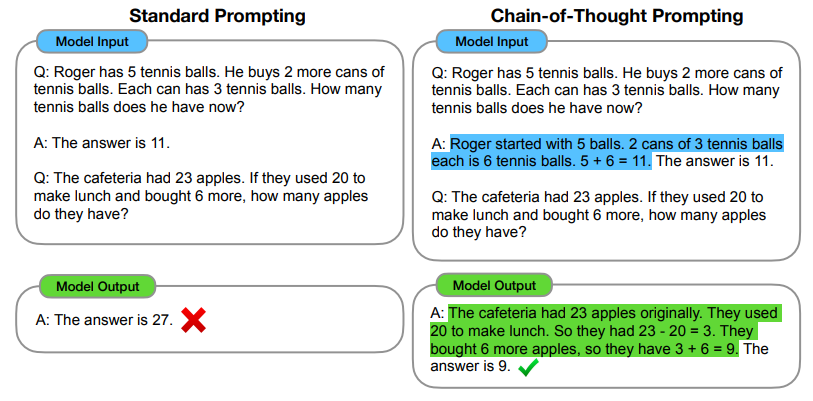

- Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models (Wei et al., Neurips 2022)

- Do Prompt-Based Models Really Understand the Meaning of Their Prompts? (Webson et al., NAACL 2022)

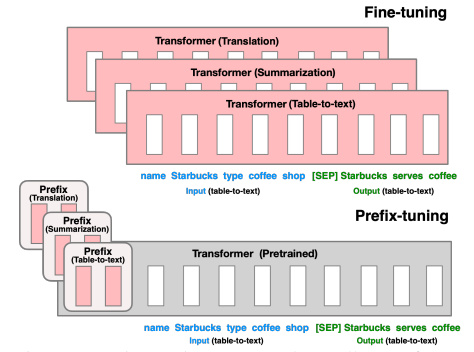

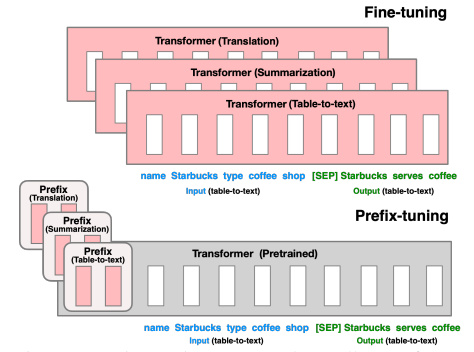

- Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation (Li et al., ACL 2021)

- The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning (Lester et al., EMNLP 2021)

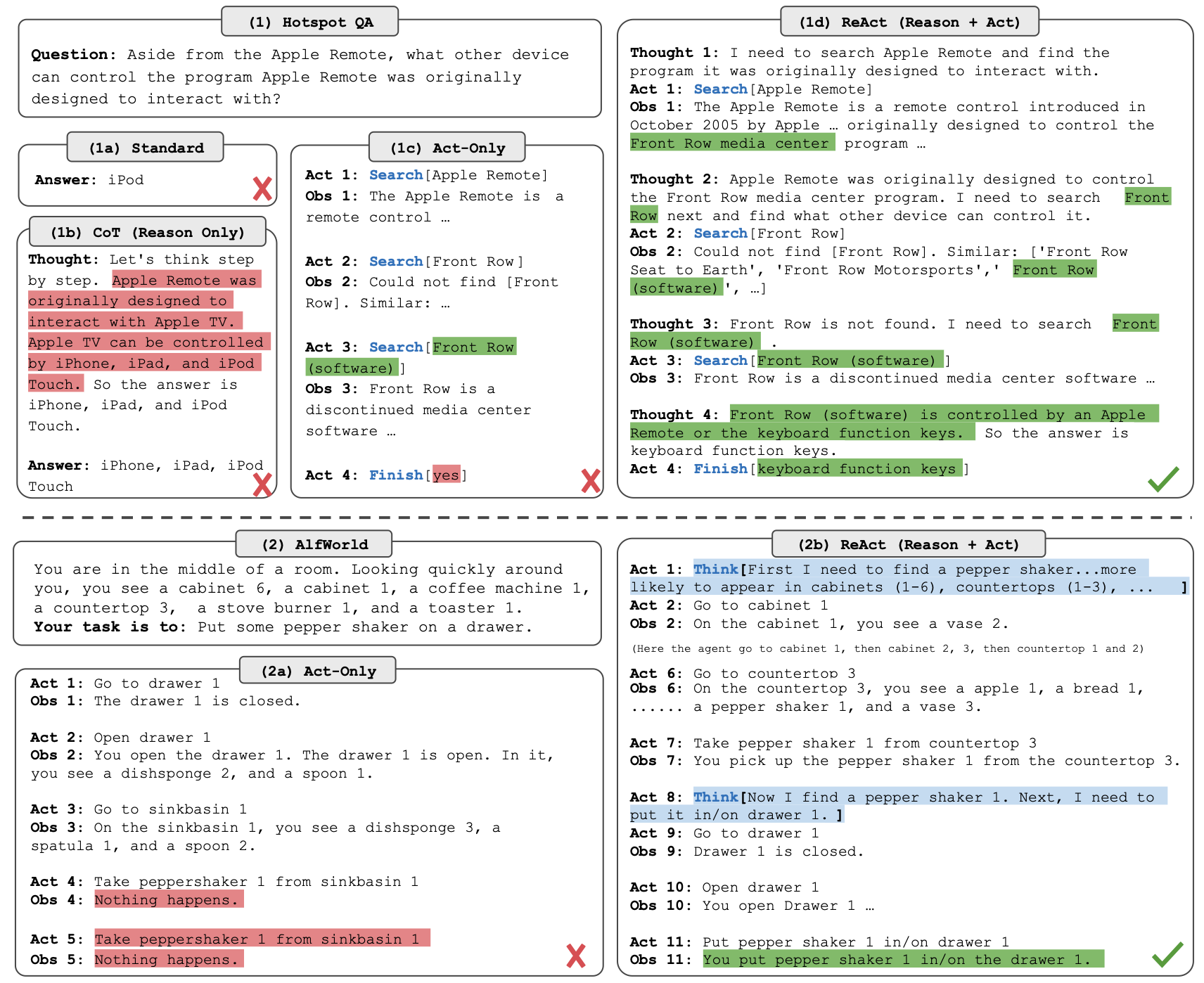

- 4. Tools-Augmented Language Model

- 5. Misc

- Task-Specific Skill Localization in Fine-tuned Language Models (Panigrahi et al., ICML 2023)

- Same Pre-training Loss, Better Downstream: Implicit Bias Matters for Language Models (Liu et al., ICML 2023)

- DoReMi: Optimizing Data Mixtures Speeds Up Language Model Pretraining (Xie et al., arxiv 2023)

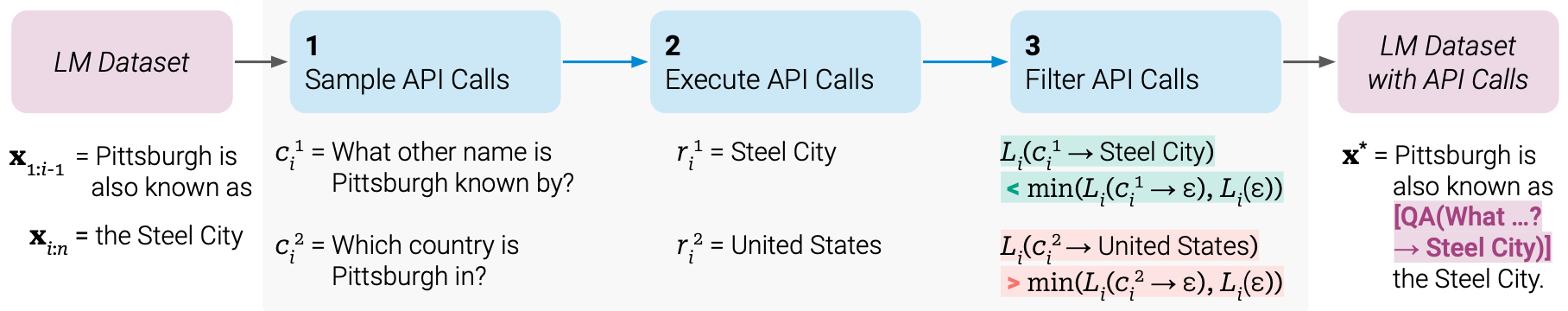

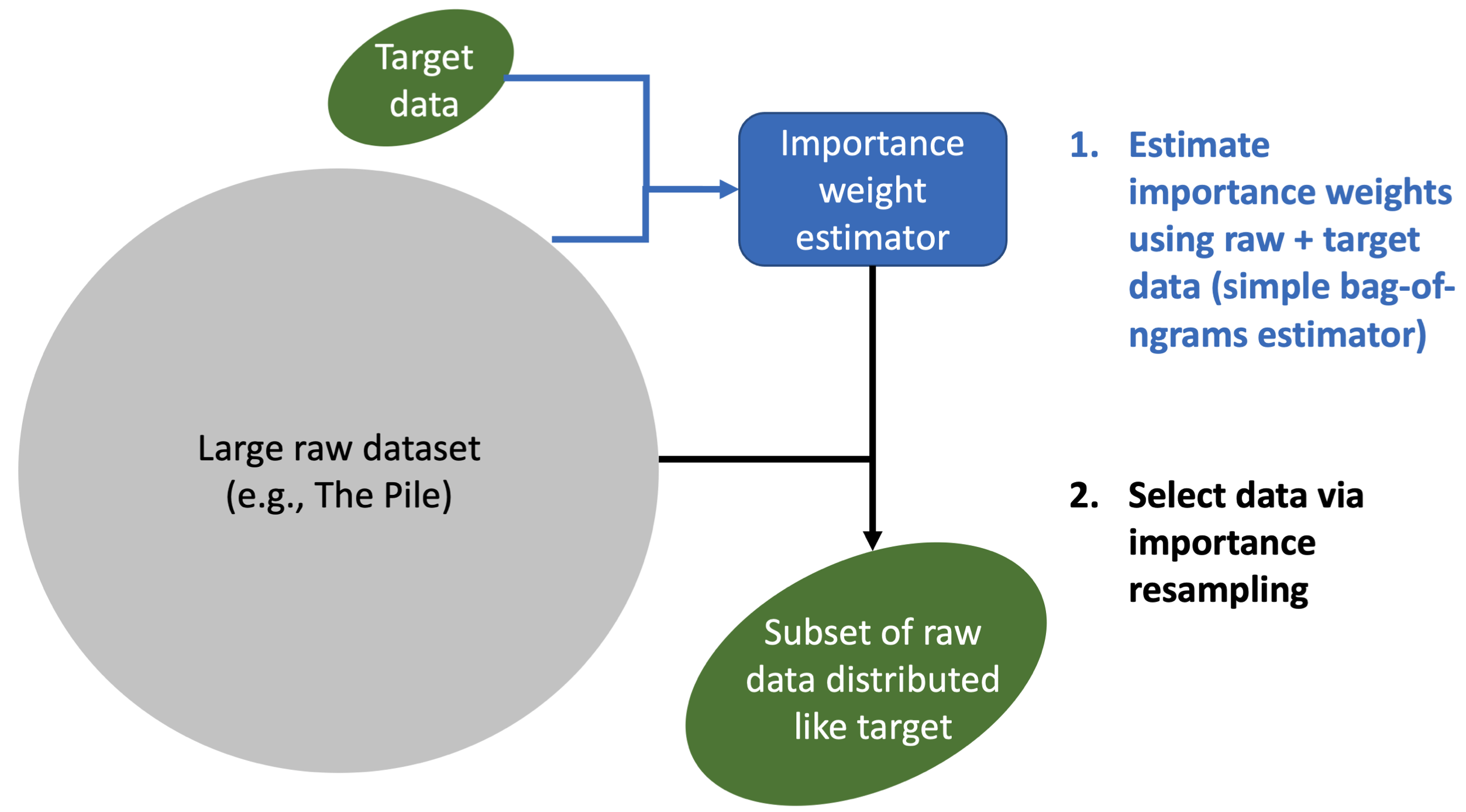

- Data Selection for Language Models via Importance Resampling (Xie et al., arxiv 2023)

- Language Models represent Space and Time (Gurnee et al., arxiv 2023)

- Can Foundation Models Wrangle Your Data? (Narayan et al., VLDB 2023)

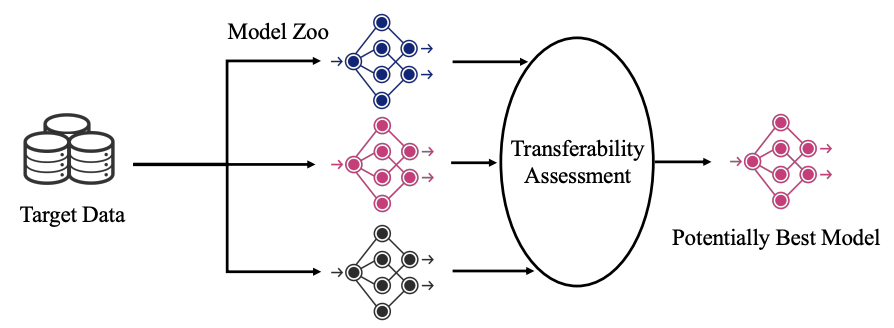

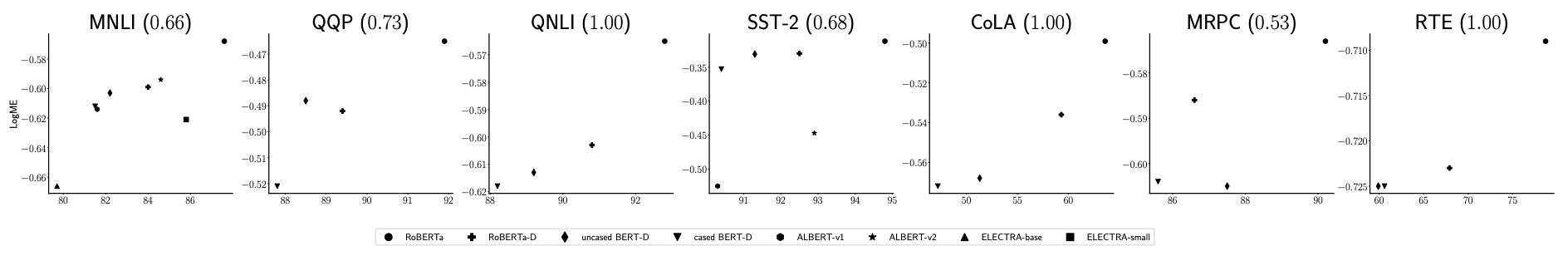

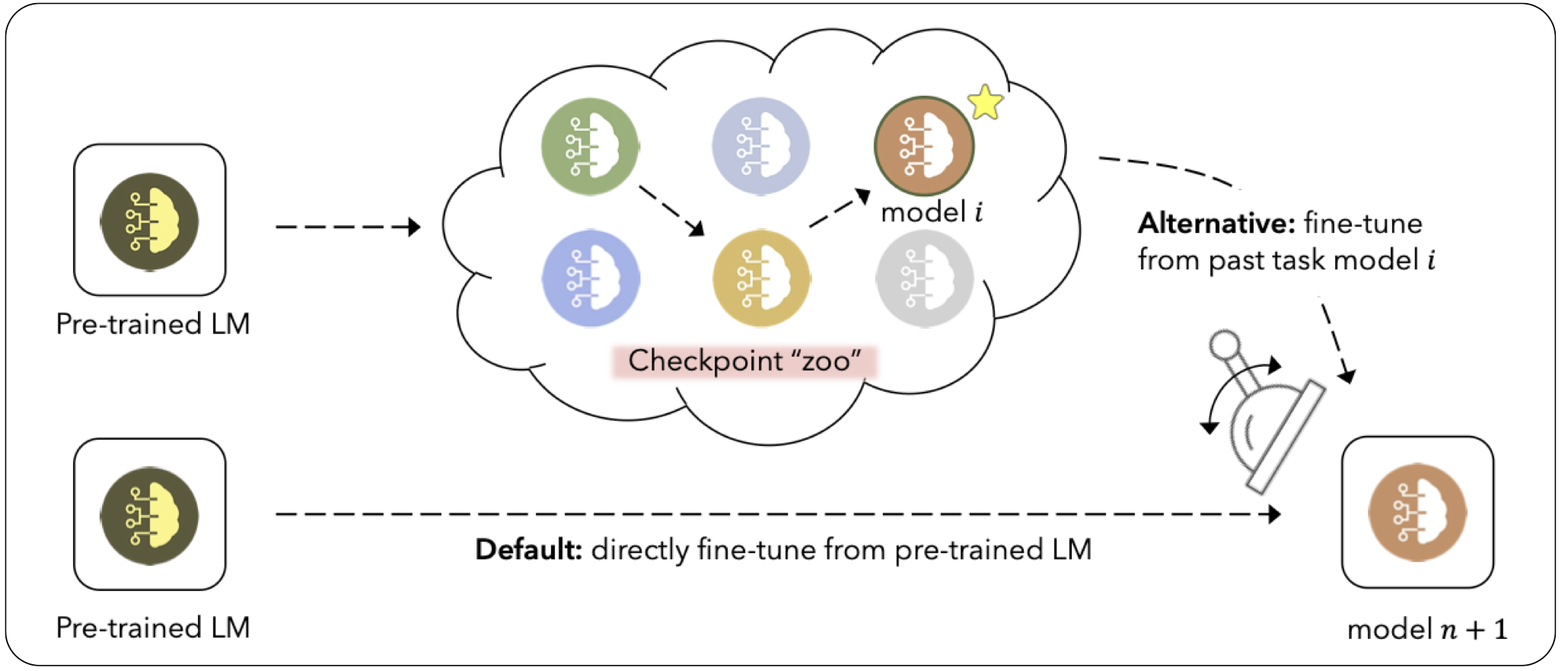

- Ranking and Tuning Pre-trained Models: A New Paradigm for Exploiting Model Hubs (You et al., JMLR 2023) + LogME: Practical Assessment of Pre-trained Models for Transfer Learning (You et al., ICML 2021)

- On Exploring the Reasoning Capability of Large Language Models with Knowledge Graphs (Lo et al., GenIR@SIGIR 2023)

- Towards Robust and Efficient Continual Language Learning (Fisch et al., arxiv 2023)

- Beyond Scale: the Diversity Coefficient as a Data Quality Metric Demonstrates LLMs are Pre-trained on Formally Diverse Data (Lee et al., ICML 2023)

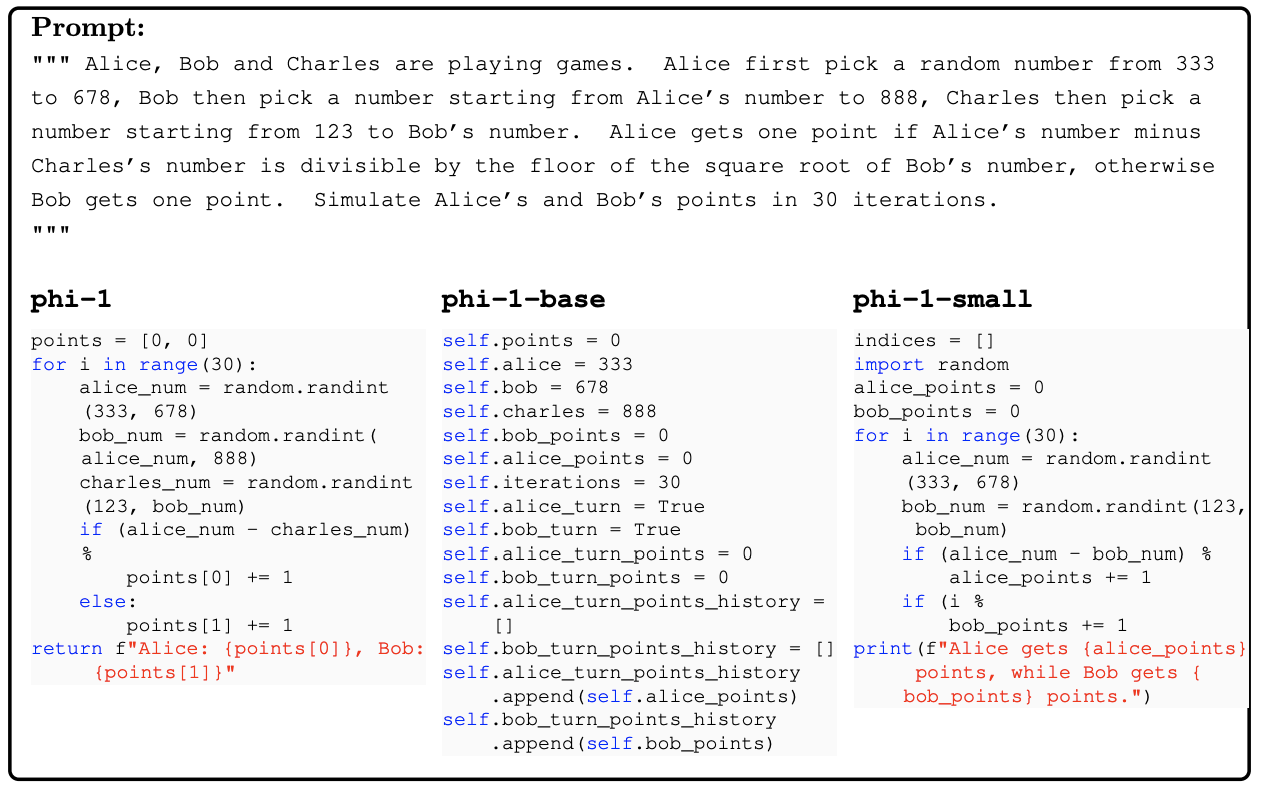

- Textbooks Are All You Need (Gunsasekar et al., arxiv 2023)

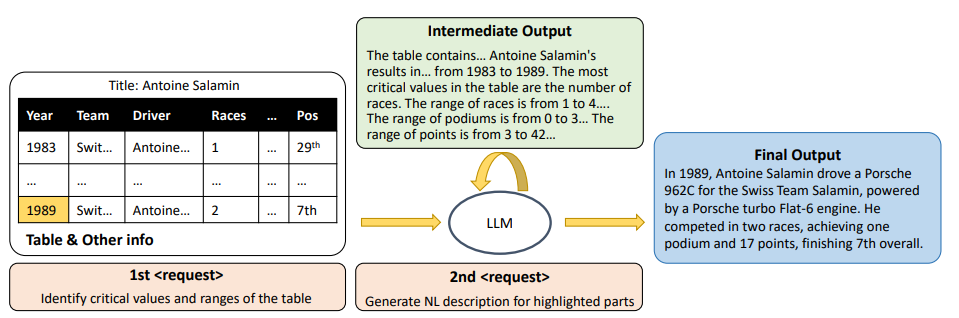

- Evaluating and Enhancing Structural Understanding Capabilities of Large Language Models on Tables via Input Designs (Sui et al., arxiv 2023)

- Benchmarking Large Language Model Capabilities for Conditional Generation (Joshua et al., ACL 2023)

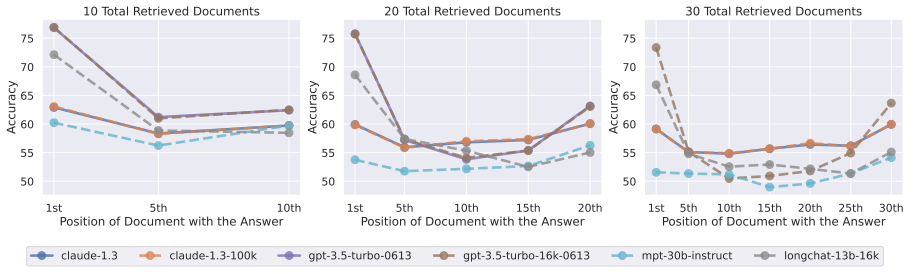

- Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts (Nelson et al., arxiv 2023)

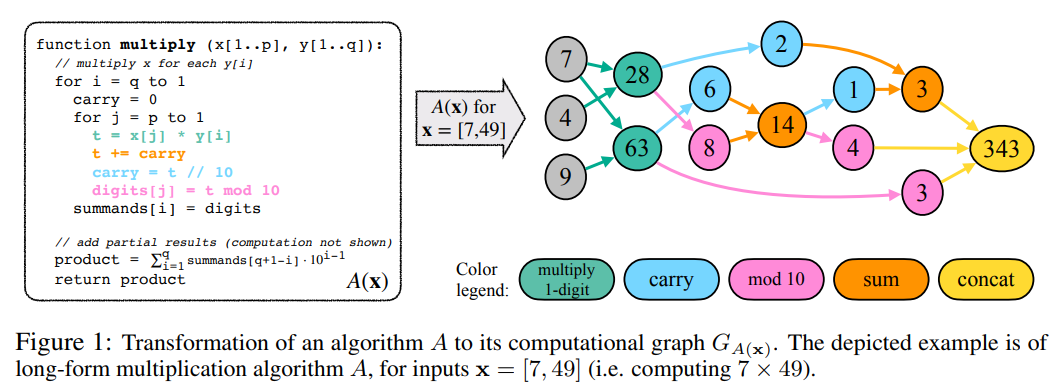

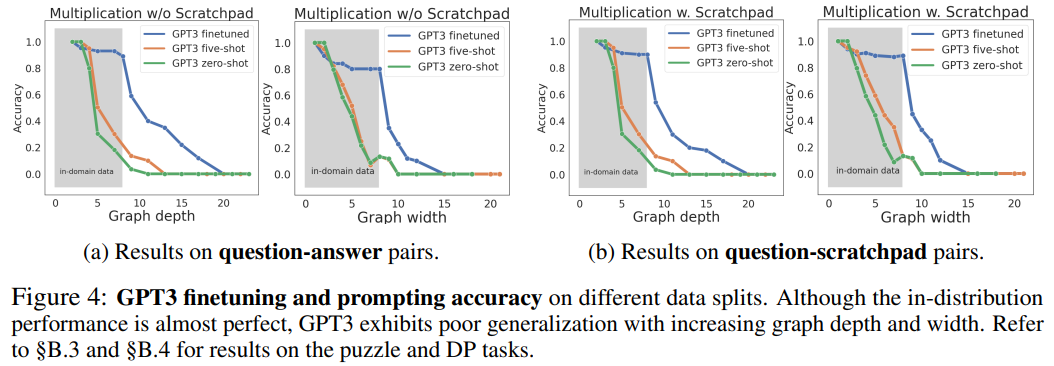

- Faith and Fate: Limits of Transformers on Compositionality (Dziri et al., arxiv 2023)

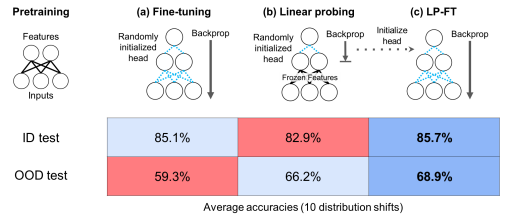

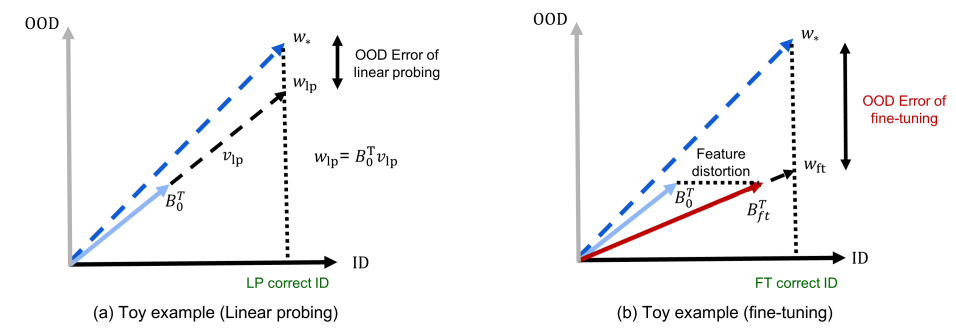

- Improving Representational Continuity with Supervised Continued Pretraining (Sun et al., arxiv 2023) + Fine-tuning can distort pretrained features and underperform out-of-distribution (Kumar et al., ICLR 2022)

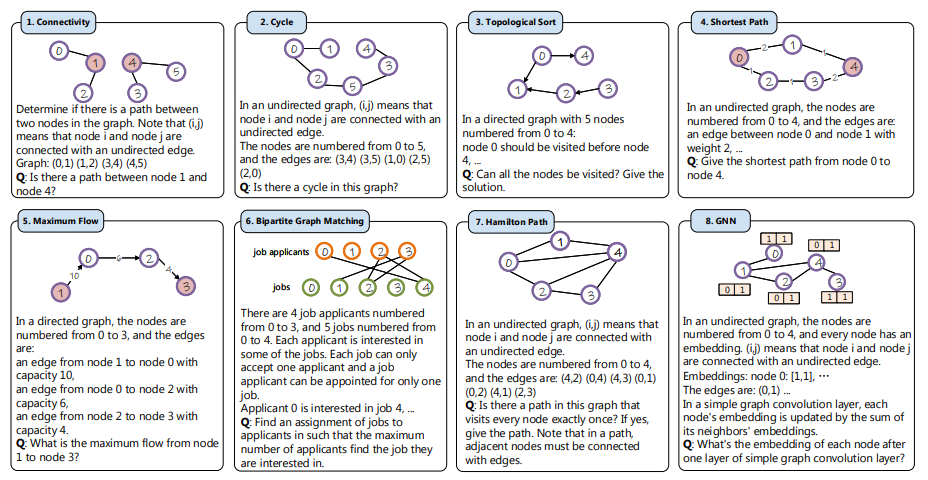

- Can Language Models Solve Graph Problems in Natural Language? (Wang et al., arxiv 2023)

- Selection-Inference: Exploiting Large Language Models for Interpretable Logical Reasoning (Creswell et al., ICLR 2023)

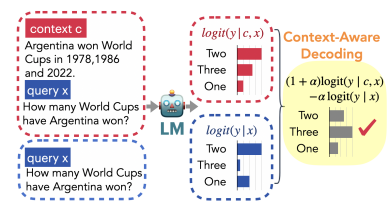

- Trusting Your Evidence: Hallucinate Less with Context-aware Decoding (Shi et al., arxiv 2023)

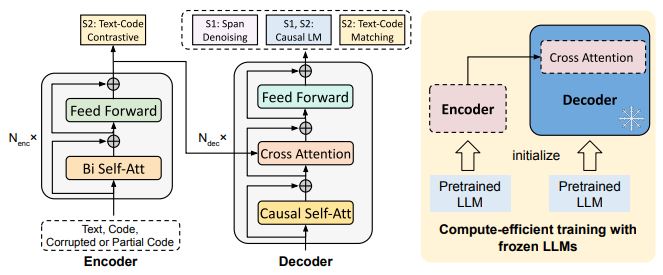

- CodeT5+: Open Code Large Language Models for Code Understanding and Generation (Wang et al., arxiv 2023)

- Emergent World Representations: Exploring a Sequence Model Trained On a Synthetic Task (Li et al., ICLR 2023).

- Quantifying Memorization Across Neural Language Models (Carlini et al., ICLR 2023)

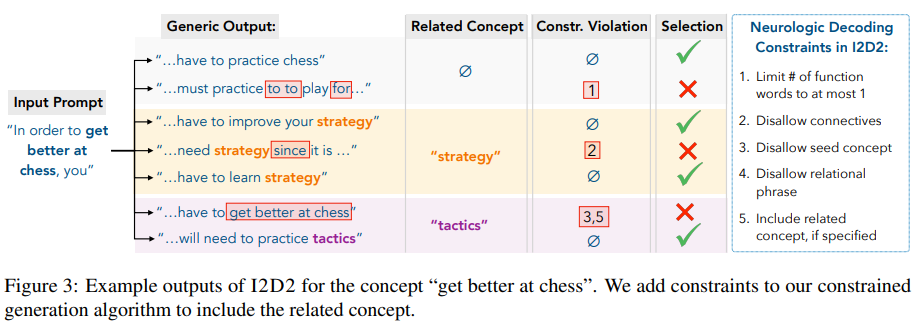

- I2D2: Inductive Knowledge Distillation with NeuroLogic and Self-Imitation (Bhagavatula et al.):

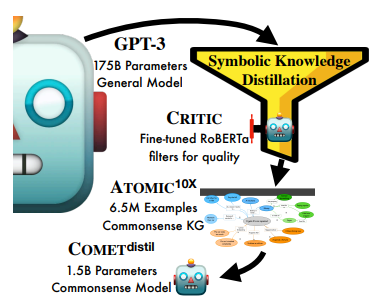

- Symbolic Knowledge Distillation: from General Language Models to Commonsense Models (West et al., NAACL 2022)

- Efficient Training of Language Models to Fill in the Middle (Bavarian et al., arxiv 2022).

- Language Models of Code are Few-Shot Commonsense Learners (Madaan et al., EMNLP 2022).

- Fast Model Editing at Scale (Mitchell et al., ICLR 2022).

- Locating and Editing Factual Associations in GPT (Meng et al., Neurips 2022).

- Understanding Dataset Difficulty with V-Usable Information (Ethayarajh et al., ICML 2022).

- A Contrastive Framework for Neural Text Generation (Su et al., NeurIPS 2022).

- The Trade-offs of Domain Adaptation for Neural Language Models (Grangier et al., ACL 2022)

- Memorization Without Overfitting: Analyzing the Training Dynamics of Large Language Models (Tirumala et al., Neurips 2022)

- From zero-shot to few-shot Text Classification with SetFit (Tunstall et al., ENLSP at Neurips 2022)

- Improving Language Models by Retrieving from Trillions of Token (Borgeaud et al., ICML 2022)

- Adapt-and-Distill: Developing Small, Fast and Effective Pretrained Language Models for Domains (Yao et al., ACL Findings 2021)

- UDALM: Unsupervised Domain Adaptation through Language Modeling (Karouzos et al., NAACL 2021)

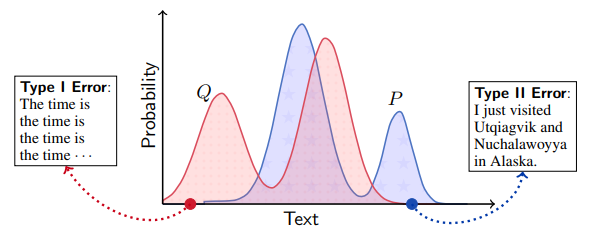

- MAUVE: Measuring the Gap Between Neural Text and Human Text using Divergence Frontiers (Pillutla et al., NeurIPS 2021).

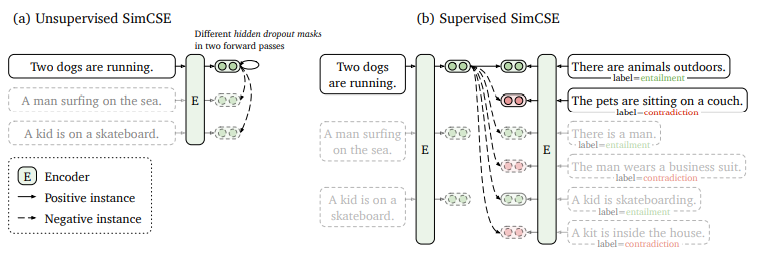

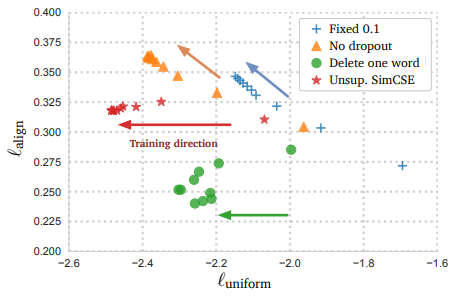

- SimCSE: Simple Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings (Gao et al., EMNLP 2021).

- Surface Form Competition: Why the Highest Probability Answer Isn’t Always Right (Holtzman et al., EMNLP 2021)

- Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation (Li et al., ACL 2021)

- The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning (Lester et al., EMNLP 2021)

- BioMegatron: Larger Biomedical Domain Language Model (Shin et al., EMNLP 2020)

- Don’t Stop Pretraining: Adapt Language Models to Domains and Tasks (Gururangan et al., ACL 2020):

- Generalization through Memorization: Nearest Neighbor Language Models (Khandelwal et al., ICLR 2020):

- When does label smoothing help?. (Müller et al., NeurIPS 2019).

- Back Translation Improving Neural Machine Translation Models with Monolingual Data (Sennrich et al., ACL 2016)

1. Knowledge Retrieval - Augmented Language Model

2023

-

Retrieval Meets Long Context Large Language Models (Xu, arxiv 2023)

The paper demonstrates the benefit of passage retrieval for both short and long context language model on 7 close book QA datasets. Several observations ares:

- Retrieval is especially useful for 4K-context LLM as the context provided for each question in 7 tasks usually exceeds 4K tokens.

- With the same retrieval passages, 16K-context LLMs exploits the passages more effectively than 4K-context LLMs, leading to better performance. Authors speculate this is because 4K-context suffers from “lost in the middle” issue while retrieval passages are only at the beginning part of 16K-context LLM.

- Retrieval is useful for both long and short-context LLMs (i.e. outperform the without-retrieval counterpart)

-

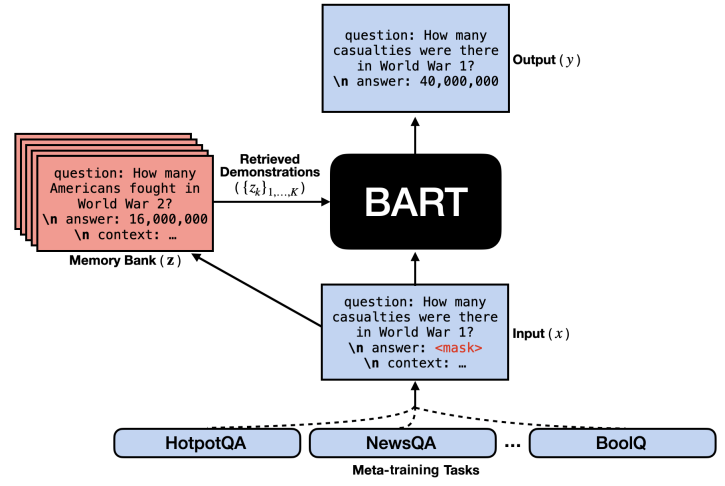

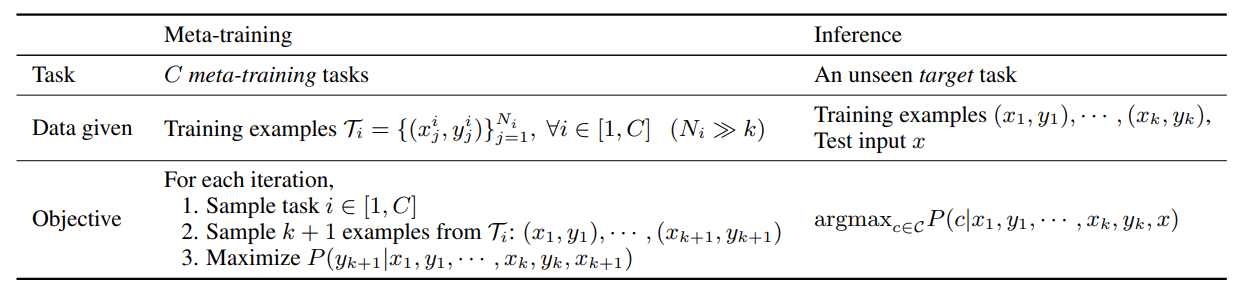

Meta-training with Demonstration Retrieval for Efficient Few-shot Learning (Mueller, Finding ACL 2023)

Inspired by MetaICL, this paper proposes few-shot meta learning with demonstration retrieval that leverages multi-task learning on a large variety of tasks, endowing small language models with better ability to generalize across different tasks and domains. The meta-training is conducted by employing a freezed dense passage retriever (i.e. RAG) to retrieve k demonstrations \(z\) for an input \(x\). Each demonstration \(z\) is then concatenated with input \(x\) and is fed into a BART-large model. The model is trained to predict the output \(y\) marginalizing over k retrieved demonstrations:

\[p (y|x) \approx \prod_{i}^{N} \sum_{k}^{K} \; p_{retriever} (z_k | x) \; p_{PLM} (y | x, z_k, y_{1:i-1})\]

(source: copied from the paper).

To adapt BART to various tasks without architectural modification, input and output are standardized according to an unified template:

Encoder: "question: ... \n answer: [MASK] \n context: \n" Decoder: "question: ... \n answer: ..."Author argues this template aligns with BART’s pre-training objective (generate both question and answer). The results stress the importance of external knowledge bank to the few-shot performance of meta-learned model.

-

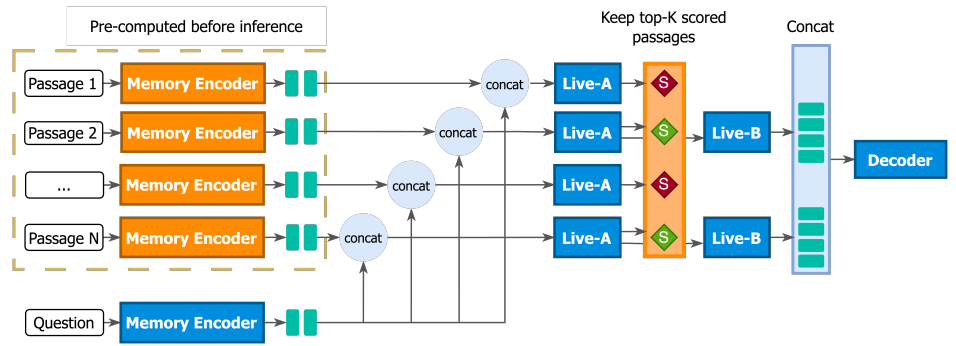

GLIMMER: generalized late-interaction memory reranker (de Jong, arxiv 2023)

LUMEN (see here) is a quality-compute trade-off solution for retrieval-augmented LM. GLIMMER is built on LUME with several improvements:

- The memory encoder is fine-tuned, instead of being frozen.

- Live fine-tuned encoder is divided into two parts:

- First N layers (Live-A) is used to re-rank retrieved passages conditioned on the input question. Top-k relevant passages are kept and passed to last M encoder layers.

- Last M layers (Live-B) updates the representation of each {question input, retrieved passage} and sends them to the decoder, similarly to LUME’s live encoder.

(source: copied from the paper).

Both memory encoder, live encoders and deocer are fine-tuned end-to-end with multi-task learning to endow components better generalization capability. The training loss is inspired Atlas’s PDist (see atlas): promote the passages that lower the generation’s perplexity to be ranked higher.

\(\mathcal{L_{pdist}} = KL (p^{rank} \; | \; p^{LM})\) where \(p^{rank} \varpropto exp(score(passage_k, \; question)/\tau)\) and \(p^{LM} \varpropto exp(log \; p_{LM} (answer \; | \; passage_k, \; question)/\tau)\)

-

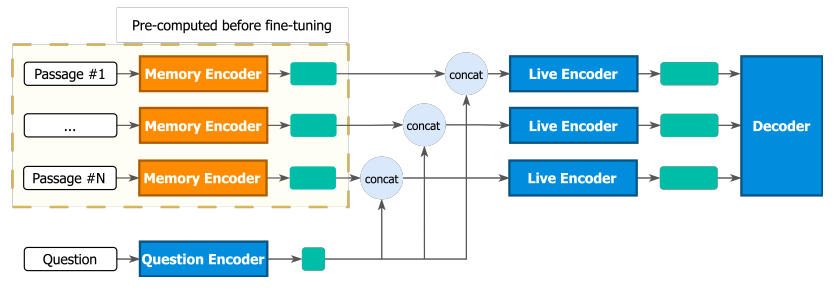

Pre-computed memory or on-the-fly encoding? A hybrid approach to retrieval augmentation makes the most of your compute (de Jong, ICML 2023)

LUMEN is a retrieval-augmented LM that neutralizes the pros/cons of Fusion-in-Decoder LM (on-the-fly-encoding) and memory-augmented LM (pre-computed memory):

- Fusion-in-Decoder (FiD) encodes the retrieved passages on-the-fly together with the input \(Enc(input, passage_i)\). Hence, it is expensive if number of retrieved passages is large.

- Memory-augmented pre-computes the embedding of passages, without taking the input into account, \(Enc(passage_i)\). Hence, the representation of each passage is input-agnostic. This method is more efficient than FiD but less powerful.

LUMEN trade-off both methods by employing a frozen large encoder to pre-compute the embeddings for the passages and a live (aka. parameters will be fine-tuned) question-encoder to encode the question. Then, another live encoder but with smaller number of parameters will update the representation of a passage conditioned on the input. Finally, the decoder performs cross-attention over {input, retrieved passage} pairs to select the most relevant one, just like in FiD. As the live encoder in LUME is much smaller than FiD, LUME is more efficient accordingly.

(source: copied from the paper).

Experiments demonstrates the LUME’s performance is very close to FiD while being much cheaper.

-

How Does Generative Retrieval Scale to Millions of Passages? (Pradeep∗ et al., GenIR@SIGIR 2023)

Differential search index (DSI) has emerged as a novel generative retrieval, deviating from common retrieve-then-rerank paradigm. While working effectively on small corpus ( O(100k) documents ), this paper has pointed that the performance of DSI when scaling to large corpus ( O(1M) documents ) is significantly degraded. Several observations:

- Synthetic queries for the fine-tuning of retrieval phase are important, as it helps to reduce the coverage gap: indexing phase sees the whole corpus while this is not the case for retrieval phase.

- In case of MSMarco, indexing phase does not yield gain.

- In case of MSMarco, using Naive IDs as Document Identifiers has strongest performance among {Atomic ID, Naive ID, Semantic ID}. However, scaling LM from T5-XL (3B) to T5-XXL (11B) causes performance drop.

Note: the paper consider only MS-Marco as large corpus, which may cause a bias in the evaluation.

-

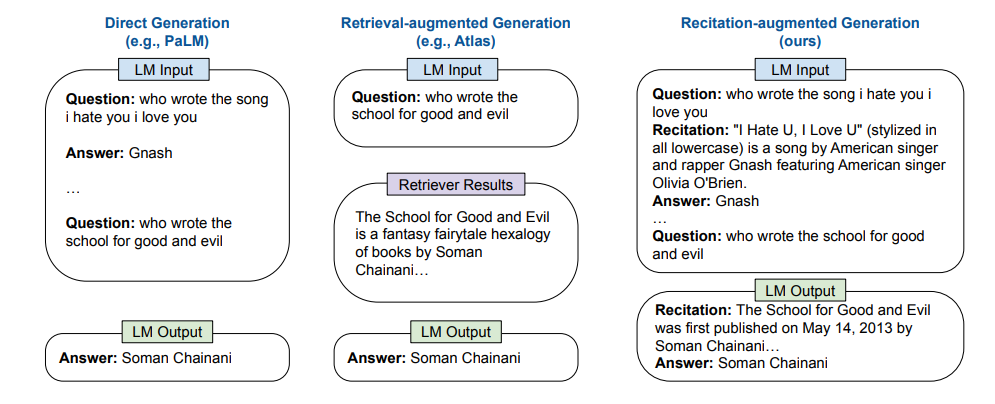

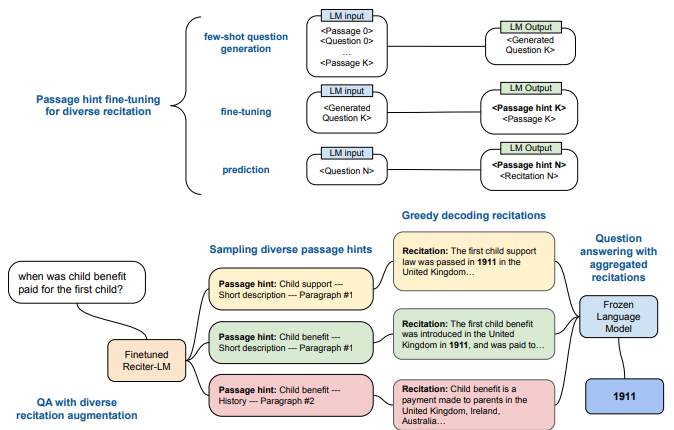

Recitation-Augmented Language Models (Sun et al., ICLR 2023)

Leveraging the memorizing ability of large language models, the paper propose RECITE, a recite-and-answer strategy for close book question answering. Instead of retrieving supports from external corpus (“open book”), the model tries to recite the relevant knowledge stored in the model parameters (“close book”) and then answer the question (in the similar way to chain-of-thought prompting).

(source: copied from the paper).

They introduces 3 RECITE settings which are all based on in-context learning:

- Recite a single passage for the question, then answer the question using the recitation.

- Self-consistency ensemble: recite multiple passages instead of one using top-k sampling, each passage leads to an answer, the final answer is decided via majority vote.

- Multiple-recite-and-answer: recite multiple passages, then concatenate them and output a single answer based on the concatenation.

- Passage hint-based diversified recitation: solution to hallucinating wrong recitation while ensuring enough diversity of generated recitations, this method proposes to recite the “hint” first which then serves as a guide to recite the associated passage appropriately. In Wikipedia, the hint of a section can be the concatenation of page title + section title.

(source: copied from the paper).

Ablation studies shows RECITE improves when number of recitations increases, and is robust to the prompt’s demonstration.

-

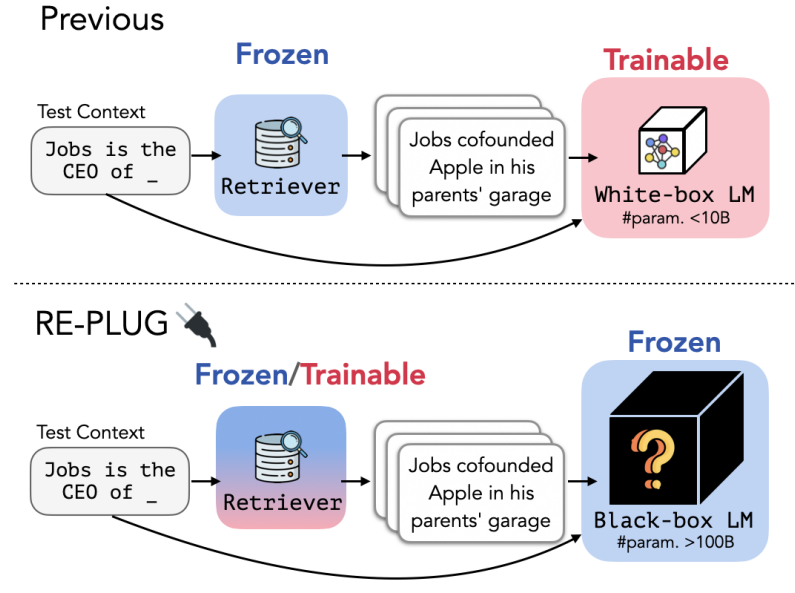

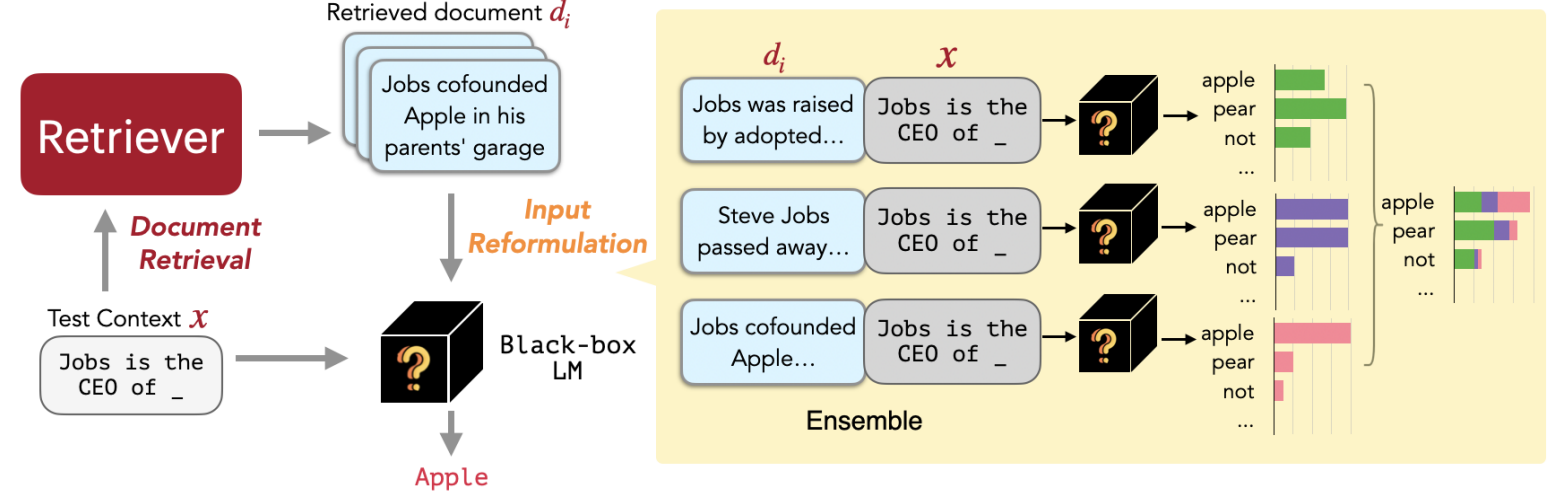

REPLUG: Retrieval-Augmented Black-Box Language Models (Shi et al., arxiv 2023)

REPLUG (Retrieve and Plug) takes another approach in retrieval-augmented LM where the LM is a black-box (hence, unknown parameters and impossible to retrain/finetune) and the retriever is either frozen or trainable. This characteristic makes REPLUG particularly flexible that it can be used with any existing LLM (yes, only large LM (>100B parameters)).

(source: copied from the paper).

The architecture of the retriever is almost the same for every retrieval-augmented LMs. It is based on dual-encoder to compute top-k documents for the input query in the embedding space. If the retriever is trainable, we then have REPLUG LSR (REPLUG with LM-Supervised Retrieval). Similarly to Atlas’s Perplexity Distillation training objective, the retriever is trained to predict how much each retrieved document would improve the black-box LM perplexity, conditioned on the query. The LM perplexity scores are normalized (via softmax) and are then distilled into the retriever to encourage the documents yielding the higher LM perplexity.

The black-box LM takes in both the input query and every retrieved document, producing a probability distribution. These distributions are combined using an ensemble method to form the final probability distribution.

(source: copied from the paper).

REPLUG can benefit rare entities.

-

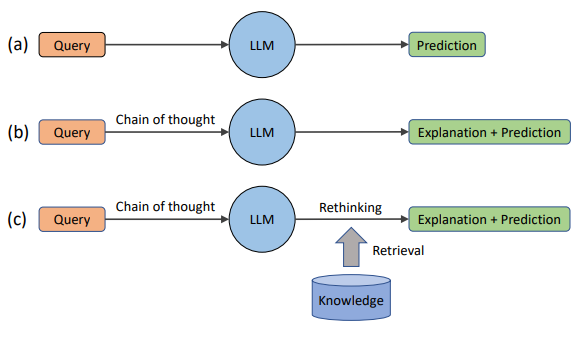

Rethinking with Retrieval: Faithful Large Language Model Inference (He et al., arxiv 2023)

The knowledge stored in the LM’s parameters may inevitable be incomplete, out-of-date or incorrect. The paper proposes rethinking with retrieval (RR), a simple post-preprocessing method that uses the a diverse set of reasoning steps obtained from the chain-of-thought prompting to retrieve relevant knowledge from external sources, to improve the the explanation, thereby, the prediction of LLMs. This approach require no additional training or finetuning and is not limited by the input length of LLMs.

(source: copied from the paper).

Specifically, for each sentence in each reasoning path, a retriever (e.g. BM25) is employed to retrieve the top-K most relevant paragraph from an external knowledge source (e.g. Wikipedia). Then, each sentence is assigned three scores:

- semantic similarity score: calculated by the maximum cosine similarity between the sentence embeddings of retrieved paragraphs and the sentence.

- entailment score and contradiction score: use a NLI model to calculate those scores assuming the most similar paragraph (according to above semantic similarity) as the premise and the sentence as the hypothesis.

The faithfulness of a reasoning path is computed using the scores of all sentences in the path. To arrive at final prediction, priority is given to the reasoning paths that exhibit higher levels of faithfulness.

rethinking with retrieval (RR) outperforms chain-of-thought prompting even when using smaller LMs.

-

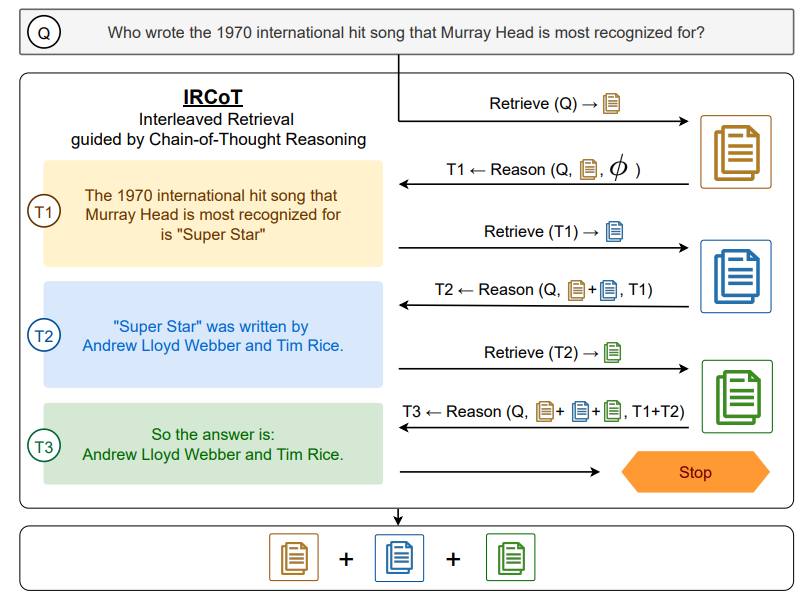

Interleaving Retrieval with Chain-of-Thought Reasoning for Knowledge-Intensive Multi-Step Questions (Trivedi et al., ACL 2023)

Interleaving Retrieval with Chain-of-Thought (IRCoT) interleaves a knowledge retriever at each reasoning step obtained from chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting to mutually guide the retrieval by CoT and vice-versa. This strategy allows to retrieve more relevant supports for later reasoning steps in the reasoning path, thereby, enhance the answer for complex multi-step reasoning question.

(source: copied from the paper).

IRCoT follows \(\textsf{retrieve-and-read}\) mechanism:

- \(\textsf{retrieve}\) step: perform interleavingly and iteratively two sub steps until the termination criterion (e.g. the phrase “the answer is” is generated in the reasoning path) is met:

- CoT-guided retrieval step (“retrieve”): using the last generated CoT sentence in the reasoning path as a query to retrieve relevant support paragraph from external knowledge source.

- Retrieval-guided reasoning step (“reasoning”): using the question, the paragraphs collected so far and the CoT sentences generated so far to generate the next CoT sentence in the reasoning path.

-

\(\textsf{read}\) step: all the support paragraphs collected from the \(\textsf{retrieve}\) step are appended to the CoT prompting as the context, asking LLM to generate the answer. The prompting template can appear like:

Wikipedia Title: <Page Title> <Paragraph Text> ... Wikipedia Title: <Page Title> <Paragraph Text> Q: <question> A: <CoT-Sent-1> ... <CoT-Sent-n>IRCoT has shown some remarkable benefits:

- IRCoT retriever outperforms (with higher recall) one-step retriever that relies solely on the question as query.

- IRCoT is also effective for smaller LMs (e.g. T5-Flan-large 0.7B). IRCoT for QA based on Flan-T5-XL (3B) even outperform GPT3 (175B) with no retriever or on-step retriever.

- Although IRCoT retriever (\(\textsf{retrieve}\) step) can itself produce the answer from its last generated CoT sentence, the \(\textsf{read}\) step where a separate QA reader is employed to consider all collected support paragraphs together is still necessary, since it yields much better accuracy.

- \(\textsf{retrieve}\) step: perform interleavingly and iteratively two sub steps until the termination criterion (e.g. the phrase “the answer is” is generated in the reasoning path) is met:

2022

-

Transformer Memory as a Differentiable Search Index (Tay et al., Neurips 2022)

Traditional Information retrieval (IR) system involves retrieve-then-rank mechanism: (i) given a query, \(k\) nearest documents are retrieved from an indexed corpus, (ii) retrieved documents are then sorted. The paper presents the Differentiable Search Index (DSI), a new paradigm for learning an end-to-end search system where the retrieve phase and the rank phase are performed within a single seq2seq neural model (e.g. T5, BART). It is shown with an appropriate design for {document representation, document identifier representation, document indexing strategy, training strategy}, DSI can obtain significant gain over state-of-the-art baselines (dual encoder, BM25):

- Document representation: a document is represented by its first \(L\) tokens.

- Document identifier representation: a document can be tagged by an unique integer, or unique \(tokenizable\) string, or semantically structured identifiers.

- Documents are indexed by training a Seq2Seq model to learn the mapping \(\textsf{doc_tokens} \rightarrow \textsf{docid}\). In other word, this task makes the model memorize which document corresponds to which identifier.

- At the same time, the model is jointly trained (under multi-task learning, similarly to T5 training style) with (\(\textsf{query, docid}\)) samples, so that at inference time, the decoder is able to generate relevant \(\textsf{docid}\) (s) for given input query.

(source: copied from the paper)

In summary, the multi-task training of DSI looks like:

Input: "Document indexing: document_tokens" --> T5 --> Output: "docid" Input: "Document retrieval: query_tokens" --> T5 --> Output: "docid" -

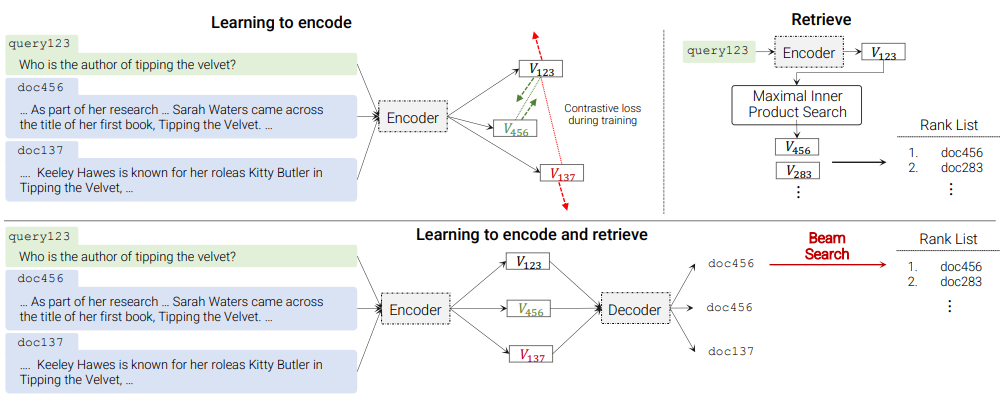

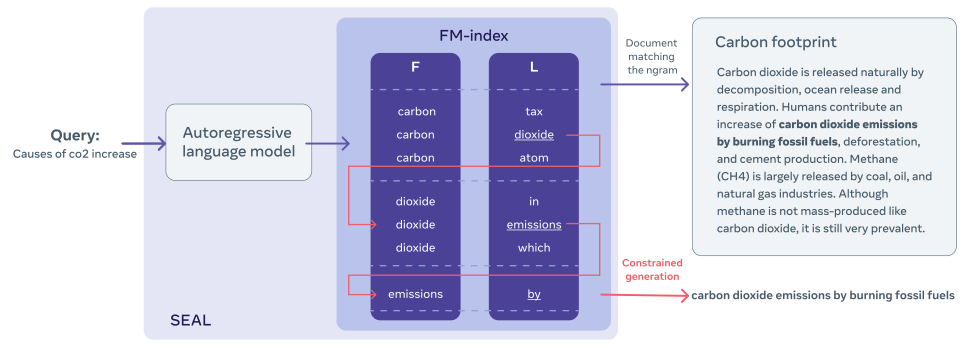

Autoregressive Search Engines: Generating Substrings as Document Identifiers (Bevilacqua et al., Neurips 2022)

Autoregressive models has emerged as the de-facto way to address the knowledge-intensive language task (KILT). This paper suggests that this kind of model also has the capability to performance the evidence retrieval with minimal intervention to the model’s architecture. The whole evidence corpus is indexed using an efficient data structure (FM index) in the way that for a given token, we can quickly figure out all possible next tokens in the corpus. The paper introduces SEAL, an autoregressive model that can directly locate the answer as well as the document containing the answer via generation constraint on FM index, for a query. It proposes a clever scoring function combining LM’s score and token’s frequency in the corpus while taking into account the fact that a document can contain multiple supports.

Ablation studies reveal:

- SEAL can work well even with small size (~400M)

- Performance increase with a larger beam search, and seems to start decreasing when the beam reaches between 10 and 15.

- Decoding maximum length is a crucial factor, where longer output sequence is more informative than shorter one.

(source: copied from the paper)

-

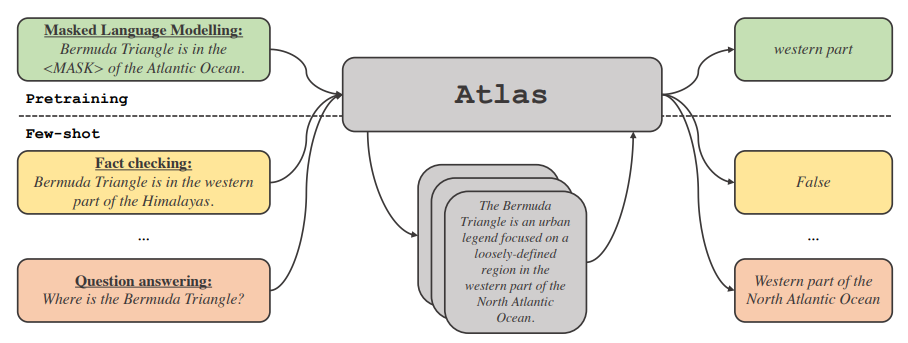

Atlas: Few-shot Learning with Retrieval Augmented Language Models (Izacard et al., arxiv 2022)

Medium LMs augmented with retrieval capability can be competitive with (or even outperform) LLMs in few-shot learning while being much more parameter-efficient. Atlas consists of a retriever and a LM that are jointly learnt with a focus on the ability to perform various knowledge intensive tasks with very few training examples.

-

Retriever: initialized from a BERT-based dual-encoder pre-trained with contrastive loss.

-

LM: all tasks are casted as text-to-text. The model is initialized from the T5-1.1-lm-adapt (trained on unlabeled text only + trained with LM objective) variants.

(source: copied from the paper)

Before fine-tuning with few-shot examples, the retriever and the LM are jointly pretrained with a set of objectives:

-

Attention Distillation (ADist): the cross-attention scores between the input documents and the output are distilled into the retriever to encourage the retrieval of documents of higher scores.

-

End-to-end training of Multi-Document Reader and Retriever (EMDR2): minimize the loss (similar to REALM):

\[log \sum_{z \in Z}{ p_{LM} (x | q, z ) * p_{retriever} (z | q) }\]where \(q\) is the input query, \(x\) is the output, and \(z\) is retrieved documents, playing as latent variable.

-

Perplexity Distillation (PDist): train the retriever to predict how much each retrieved document would improve the LM perplexity, conditioned on the query. The LM perplexity scores are normalized (via softmax) and are then distilled into the retriever to promote the documents yielding the higher LM perplexity at later stage.

-

Leave-one-out Perplexity Distillation (LOOP): if removing one of the retrieved documents, how much it affects the prediction of the LM.

-

Prefix language modelling: divide the sentence into two parts, taking first part as input and predicting the second part.

-

Masked language modelling: similar to T5.

The experimentation show Perplexity Distillation and Mask language modelling to be more stable than other objectives.

As retriever’s parameters are updated every training step, re-calculating the embedding and re-indexing the whole collection of documents is significantly computationally expensive (or even impossible), Atlas propose several efficient index update: (i) re-indexing the collection of document embedding every \(k\) epoch; (ii) instead of re-indexing the whole collection, only perform on top-k documents return; or (iii) freeze the index of documents.

A remarkable feature of retrieval-augmented model is that their knowledge can be kept up-to-date without retraining, by simply maintaining a collection of documents. -

-

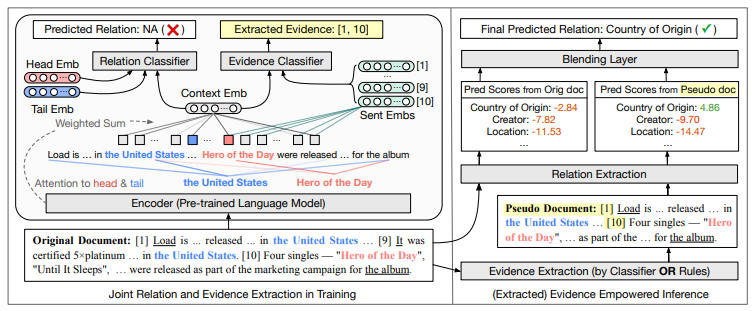

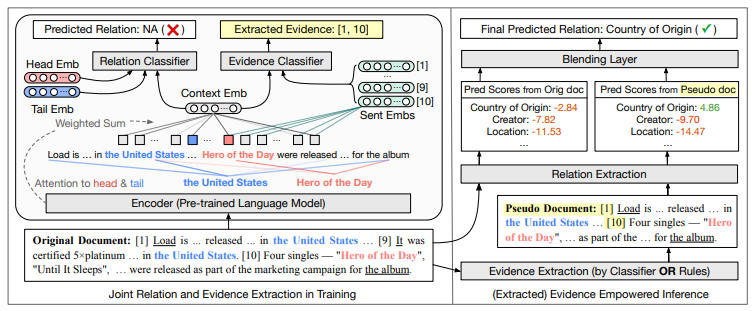

EIDER: Empowering Document-level Relation Extraction with Efficient Evidence Extraction and Inference-stage Fusion (Xie et al., ACL Findings 2022)

EIDER: Extracted Evidence Empowered Relation Extraction

(source: copied from the paper)

Typical document-level relation extraction models rely on the whole document to infer the relation of an entity pair in the document. On the one hand, a minimal set of sentences (i.e. evidences) in the documents is enough for human to annotate the relation, taking the whole document as input may add noise and ambiguity to the model. On the other hand, there is no way to extract such minimal set perfectly, leading to missing important information. EIDER alleviates both aspect by introducing:

- Joint training of relation extraction end evidence sentence extraction: a base encoder is employed to learn the representation of the relation from the counterparts of the head entity, tail entity and the whole document \(p(r \mid e_h, e_t, c_{h,t})\), as well as to learn the representation of each evidence sentence \(s_n\) given the head and tail entity \(p (s_n \mid e_h, e_t)\). For the training, evidence sentences for each entity pair in a document can be either manually provided, or extracted using simple heuristics (e.g. a sentence containing both head and tail entities is considered as an evidence for this entity pair).

- Fusion of evidence in Inference: the score of each candidate relation is given by two inferences: one with the prediction from the whole documents, one with the prediction from the set of extracted evidence sentences (a subset of original document). \s

-

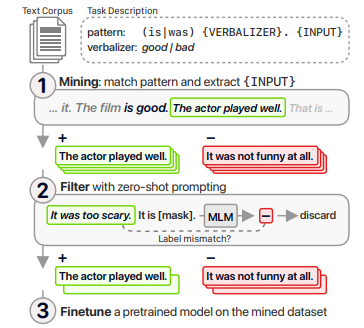

Don’t Prompt, Search! Mining-based Zero-Shot Learning with Language Models (van de Kar et al., EMNLP 2022)

\(\textsf{Generate-filter-finetune}\) approach for zero-shot learning

(source: copied from the paper)

The paper introduces a retrieval augmented zero-shot learning method which is more flexible and interpretable than prompting methods. The present method is reliant on an unlabeled corpus playing as knowledge source (e.g. the corpus used for pretraining), a regex-like mining pattern and a set of verbalizer that represents a downstream task (similar to prompting), such as \(\textsf{(is} \mid \textsf{was) \{VERBALIZER\}*. \{INPUT\} }\) for sentiment analysis where \(\textsf{VERBALIZER} \in\) \(\textsf{\{good, great, awesome, etc\}}\) for positive label and \(\textsf{\{bad, awful, terrible, etc\}}\) for negative label. It consists of 3 steps:

- Using the regex-based mining pattern to extract training samples from the unlabeled corpus. For example, given the pattern above, the sentences following “is good” or “was good” are examples of the positive class, and the sentences following “is bad”, “was bad” are examples of the negative class.

- As mined samples can be noisy, they are filtered by zero-shot prompting. Specifically, samples in which predicated label by zero-shot prompting and the mined label do not match will be removed.

- The mined dataset is then used to finetune a pretrained LM for the downstream task. Intuitively, the original zero-shot learning is casted as full finetuning with the help of mined dataset.

Experimented on sentiment analysis, topic classification and NLI tasks, mining approach outperforms zero-shot prompting method when using the same verbalizers and comparable patterns. It can partly explain the performance of prompting method using the fact that many task-relevant examples are seen during the training which can be explicitly retrieved through simple regex mining pattern.

-

SKILL: Structured Knowledge Infusion for Large Language Models (Moiseev et al., NAACL 2022)

The paper introduces SKILL a simple way to inject knowledge from structured data, such as a KG, into a language model, that can benefit knowledge-retrieval-based downstream tasks. SKILL continue to pretrain LLM directly on structured data (e.g. triples in KG) with salient-term masking without synthesizing them into equivalent natural sentences (e.g. KELM) as they found that the two approaches are competitive with each other.

SKILL demonstrates better performance than original LMs on Wikidata-related QA benchmarks as it is pre-trained on Wikidata triples. Most of the gains comes from the ability to memorize KG triples during the training. As a consequence, the model can perform very well on 1-hop questions that are supported by single triples, such as “When was Elon Musk born ?” corresponds to the triple <Elon Musk, date of birth, ?>. However, when it comes to answering multi-hop questions (e.g. “Who worked at the companies directed by Elon Musk ?” may correspond to two triples <Elon Musk, owner of, ?x> and <?y, employer, ?x> ) which requires not only the memorizing ability but also the reasoning ability, SKILL performs just slightly better than original LMs. The author points out one limitation of SKILL is that the training relies on a random set of independent triples, lacking of topological structure exploitation of a KG describing how triples are connected. Addressing this issue can improve the multi-hop QA tasks.

2021

-

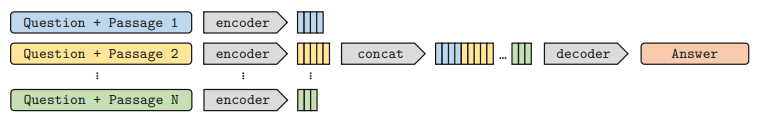

Leveraging Passage Retrieval with Generative Models for Open Domain Question Answering (Izacard et al., EACL 2021)

Retrieved evidence fusion in decoder (Fusion-in-Decoder).

(source: copied from the paper)

To address the Open Domain Question Answering, firstly, an independent knowledge retriever is leveraged to retrieve supporting passages for the input question, then, a seq2seq model (T5) takes as input the combination of the input question and supporting passages to produce the answer. Specifically, each retrieved passage concatenated with the input question is independently encoded by the encoder and their representations are merged together before sending to the decoder, in this way, the decoder can attend over the whole set of retrieved potential evidences and rely on them to generate the answer. There are two advantages of this fusion-in-decoder method:

- Avoid encoding all retrieved passages and the input question in one place which is very costly due to significant lengths of the passages.

- Thanks to the first point, we can efficiently increase the number of retrieved support passages, leading to the higher accuracy in the answer.

2020

-

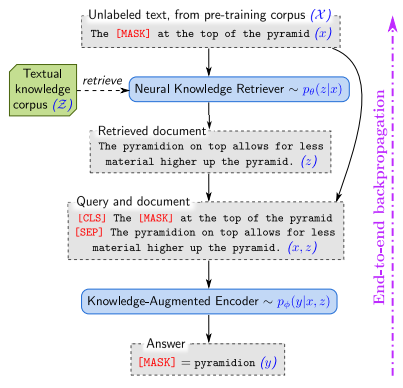

REALM: Retrieval-Augmented Language Model Pre-Training (Guu et al., ICML 2020)

Knowledge Retriever jointly pre-trained with LM.

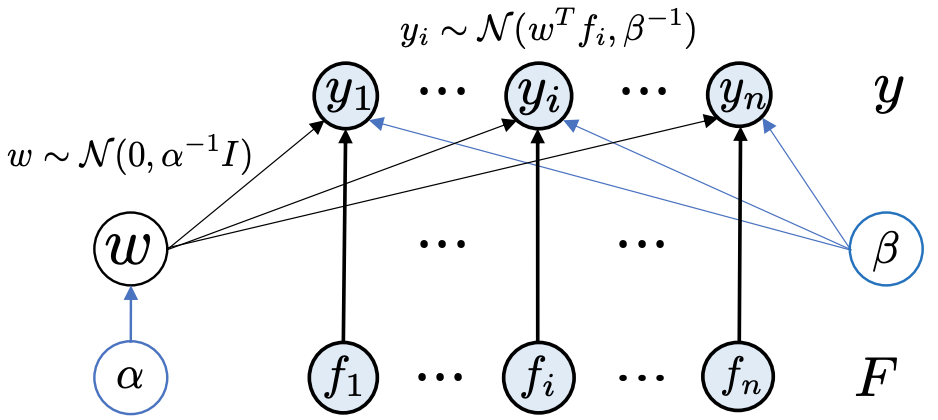

BERT-style LM is pre-trained to denoise a corrupted input sentence \(\hat{x}\) by predicting the masked tokens [MASK] in \(\hat{x}: p(x| \hat{x})\). For example, given “The [MASK] is the currency of the United Kingdom” as \(\hat{x}\), then the answer for [MASK] is “pound”. REALM makes the prediction more interpretable by first retrieving possibly helpful documents \(z\) (\(z\) plays as latent variable) from a knowledge source \(Z\) and using them (as evidences) to support the prediction of [MASK], as following:

\[p(x \mid \hat{x}) = \sum_{z \in Z}{ p (x | \hat{x}, z ) * p (z | \hat{x}) }\]\(p (x \mid \hat{x}, z )\) helps to inform which documents \(z\) contribute the most to [MASK] tokens. The knowledge retriever \(p_{\theta}(z \mid \hat{x})\) and knowledge-augmented encoder \(p_{\phi}(x \mid \hat{x}, z )\) are modelled separately using two different BERT\(_{\theta}\) and BERT\(_{\phi}\). Document \(z\) is represented by its title and body. \(p_{\theta}(z \mid \hat{x})\) involves the cosine similarity between the sentence embedding produced by BERT\(_{\theta}\) of \(\hat{x}\) and \(z\). During the pre-training, the marginal \(p(x \mid \hat{x})\) requires a summation over all documents \(z\) in \(Z\) which is very costly. Also, as \({\theta}\) changes every training step, hence the embeddings Emb(z) of all documents \(z\) in \(Z\) need to be recalculated every step \(\rightarrow\) sound impossible. To deal with these issues, REALM proposes two training strategies

- \(p_{\theta}(z \mid \hat{x})\) is marginalized over only top-K documents \(z\) instead of all. Top-K relevant documents \(z\) w.r.t. input \(\hat{x}\) can be efficiently performed by Maximum Inner Product Search (MIPS) algorithm where the embeddings of \(z\)(s) are pre-computed and pre-indexed.

- The Emb(z) are freezed for an amount of time and are only re-calculated every several hundred update step.

(source: copied from the paper)

Regarding the training setting, the model is trained using masked-language modelling. They found that masking salient terms instead of masking random span could significantly improve the performance on downstream tasks.

-

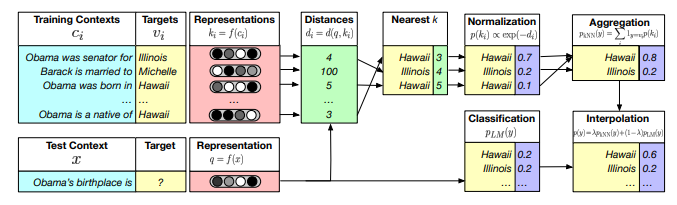

Generalization through Memorization: Nearest Neighbor Language Models (Khandelwal et al., ICLR 2020):

The paper hypothesizes that the representation learning problem may be easier than the prediction problem. For example, two sentences Dickens is the author of and Dickens wrote will essentially have the same distribution over the next word, even if they do not know what that distribution is. Given a sequence of tokens \(x = (w_1,...,w_{t-1})\), \(k\) nearest neighbors \(\mathcal{N}\) of \(x\) is retrieved from a pre-built catalog \(\mathcal{C}\) by comparing the sentence embedding of each sequence in Eclidean space. Each nearest neighbor \(x_i\) of \(x\) has a next token \(y_i\): \((x_i, y_i) \in \mathcal{N}\). The distribution of the next token \(y\) of \(x\) can be estimated via a simple linear regression: \(p_{kNN} (y \mid x) = \sum_{(x_i, y_i) \in \mathcal{N}} softmax (\mathbb{1}_{y=y_i} exp (-d (\textsf{Emb}(x), \textsf{Emb}(x_i))))\).

The LM distribution of a token \(y\) \(p_{LM} (y \mid x)\) given \(x\) is then updated by the nearest neighbor distribution \(p_{kNN} (y \mid x)\): \(p (y \mid x) = \lambda p_{kNN} (y \mid x) + (1-\lambda) p_{LM} (y \mid x)\).

(source: copied from the paper)

Several advantages of nearest neighbor LM:

- No additional training required.

- Long-tail patterns can be explicitly memorized in the pre-built catalog \(\mathcal{C}\) instead of encoded implicitly in model parameters. New domain can be adapted to LM by creating a new catalog for the target domain dataset.

- \(k\) nearest neighbor search in the embedding space of word sequences can be efficiently done using FAISS index.

2. Information Extraction

2023

-

How to Unleash the Power of Large Language Models for Few-shot Relation Extraction? (Xu et al., SustaiNLP@ACL 2023)

-

GPT-RE: In-context Learning for Relation Extraction using Large Language Models (Wan et al., arxiv 2023)

-

Universal Information Extraction as Unified Semantic Matching (Lou et al., AAAI 2023)

-

StructGPT: A General Framework for Large Language Model to Reason over Structured Data (Jiang et al., arxiv 2023)

-

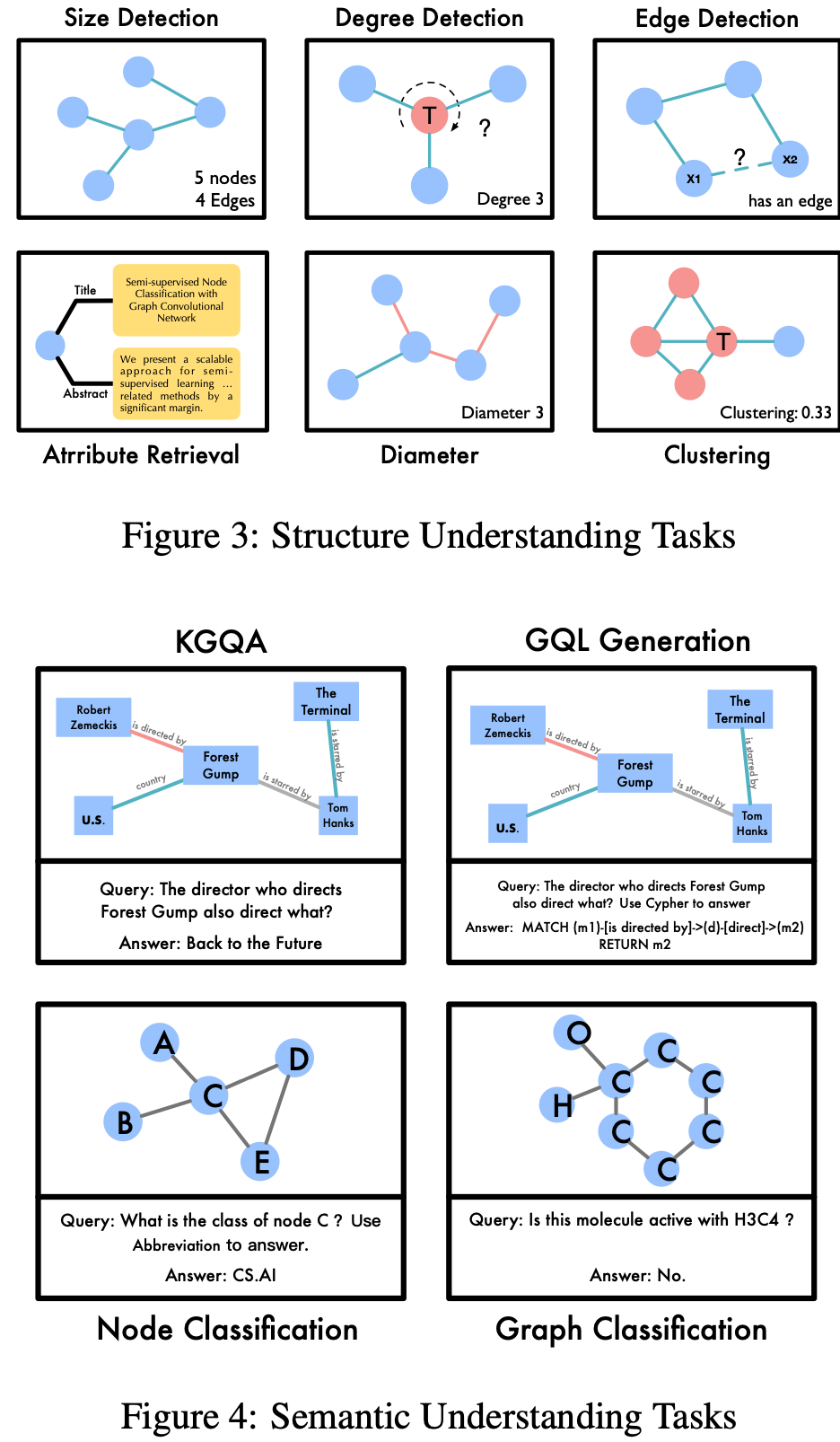

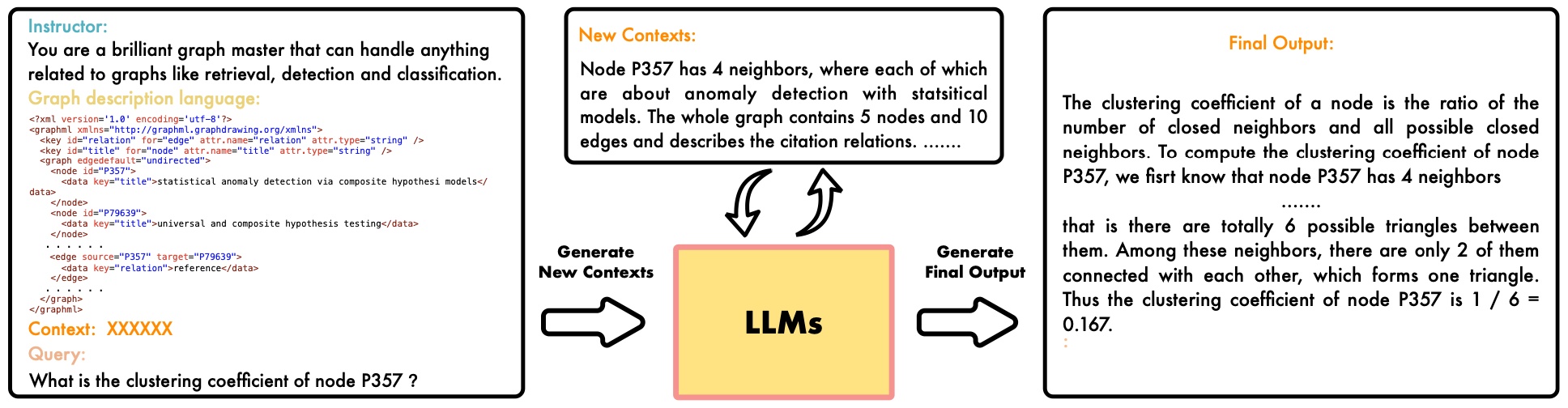

GPT4Graph: Can Large Language Models Understand Graph Structured Data? An Empirical Evaluation and Benchmarking (Guo et al., arxiv 2023)

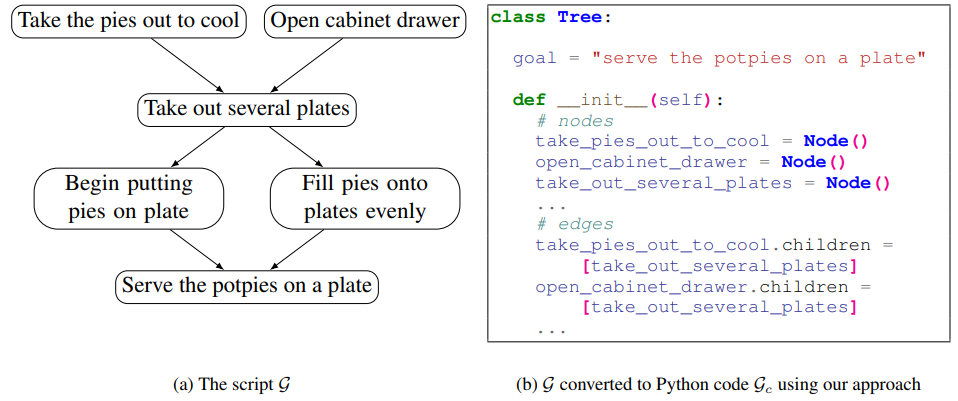

The paper presents a graph understanding benchmark to evaluate the capability (0-shot and 1-shot) of LLM (i.e. InstructGPT3,5) in comprenhending graph data. The benchmarking tasks are classified into 2 categories: structure understanding and semantic understanding, as below:

(source: copied from the paper)

Several findings:

- Input design (e.g. order of graph and question, format explaination) has a significant impact.

- Role prompting is beneficial: explicitly ask the model to summarize the graph, then use it as new context, combine with initial prompt for the target task.

(source: copied from the paper)

-

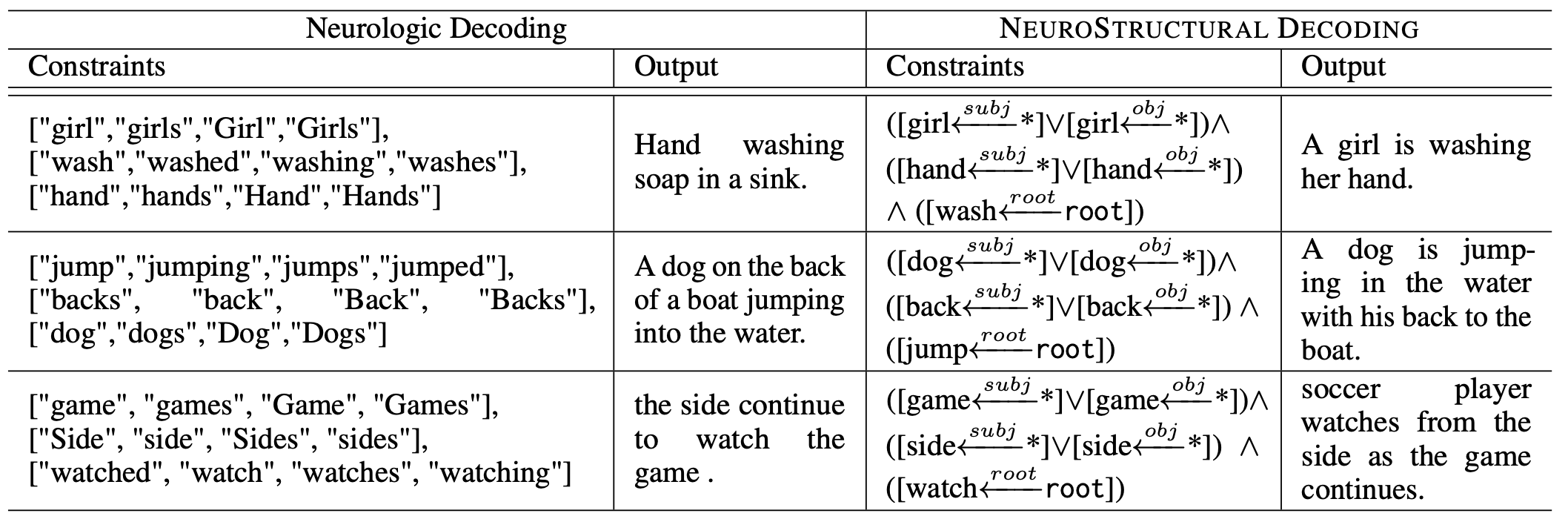

NEUROSTRUCTURAL DECODING: Neural Text Generation with Structural Constraints (Bastan et al., ACL 2023)

NeuroStructural Decoding is a new beam-search based decoding scheme in generative LLMs that guides the model to follow given structural constraints when generate the output.

(source: copied from the paper)

Structural constraints considered in this work are classified into three types:

- Unary Constraint: constraints the role of a single word in generated text such as D = (ball, obj): the word ball should appear as an object of some verb.

- Binary Constraint: constraints the relation between two words such as D = (team, subj, run): the word team should be the subject of the word run.

- Triplet Constraint: a triplet, such as D = (team, run, field) should appear in the generated text.

At each decoding step, the score of a token is modified as: \(P_{\theta} (y | x) - \lambda \sum_{i=1}^{k} ( 1 - C_i)\) where the second term pernalizes the token that does not satisfies a clause \(i\) consisting of disjunctive constraints (\(C_i = 0\)), if sastified, \(C_i = 1\).

To effectively search for relevant tokens in a beam at each decoding step, NeuroStructural Decoding tracks the states of each clause, whereby prune the paths that irreversibly violate a constraint or group paths that share irreversiby satisfied clauses. To evaluate whether partially generated text holds a syntactic constraint, it needs a syntactic parser that is capable of parsing incomplete sentence. To this end, author continues to train a dependency parser on incomplete sentence to improve its performance on such pattern.

-

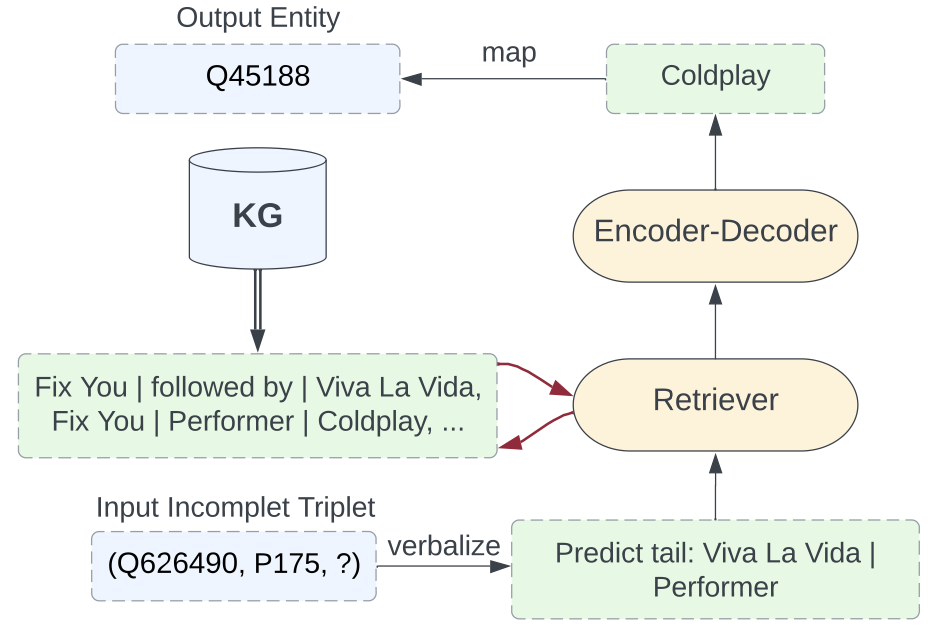

Retrieval-Enhanced Generative Model for Large-Scale Knowledge Graph Completion (Yu et al., SIGIR 2023)

ReSKGC is a retrieval-augmented generative model for KG completion. It consists of two steps:

- retrieval: the KG’s triplets and input tripet with to-be-predicted object (s, p, ?) is linearized into text (see figure below). Then, the input is used to retrieve $k$ relevant KG’s linearized triplets using non-parametric retriever BM25.

- fusion-in-decoder (FiD): a FiD is employed to encode efficiently the concatenation of retrieved passages and the input, whereby generate the missing object in the triplet (s, p, ?). ReSKGC attains the new sota performance on Wikidata5M and WikiKG90Mv2 benchmarks.

(source: copied from the paper)

-

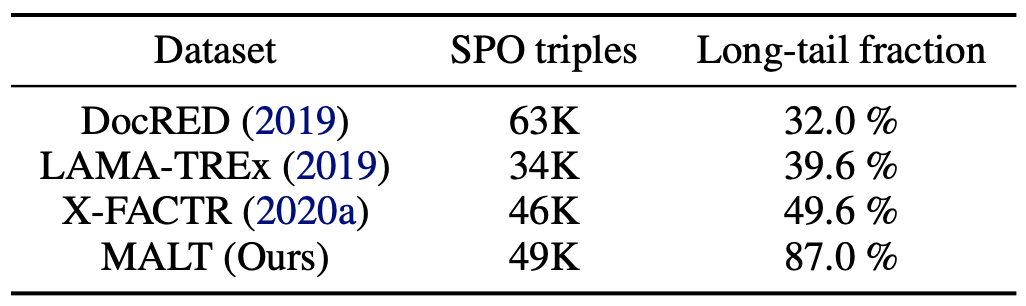

Knowledge Base Completion for Long-Tail Entities (Chen et al., arxiv 2023)

MALT is a dataset for KB completion that focuses on long-tail entities and is extracted from Wikidata. Long-tail entities are defined as being involved in less than 14 triples in KG. The dataset contains 3 entity types (i.e. business, musicComposition and human) and 8 associated predicates such as foundedBy, placeOfBirth.

(source: copied from the paper)

-

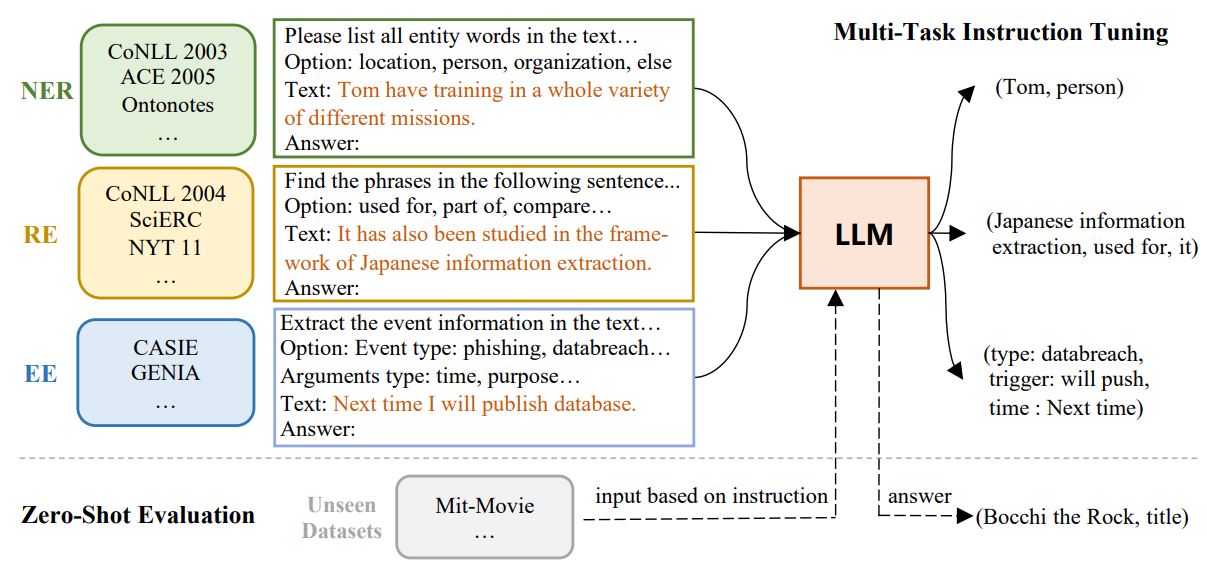

InstructUIE: Multi-task Instruction Tuning for Unified Information Extraction (Wang et al., arxiv 2023)

(source: copied from the paper)

InstructUIE gathers 32 public datasets covering three IE tasks: NER, RE, EE and transform each sample in each dataset into text-2-text-with-instruction format (see figure above). They then fine-tune a FLAN-T5 11B on those datasets. InstructUIE demonstrates better performance than UIE and USM on in-domain test set and than GPT-3-davinci or ChatGPT (for RE task) on out-of-domain test set.

-

Unifying Molecular and Textual Representations via Multi-task Language Modelling (Christofidellis et al., ICML 2023)

-

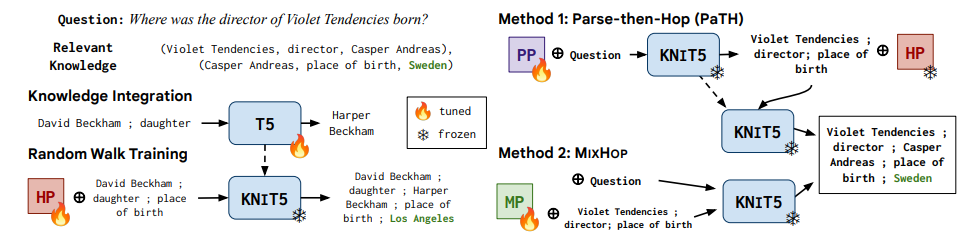

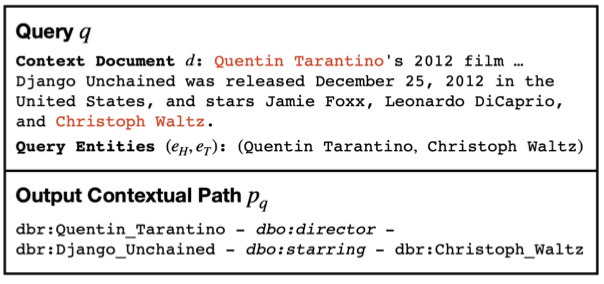

Triggering Multi-Hop Reasoning for Question Answering in Language Models using Soft Prompts and Random Walks (Misra et al., Findings ACL 2023)

LM can perform well with KG-based one-hop Q/A thanks to its ability to memorize injected triples. However, for two-hop Q/A, the model finds difficult to combine separate triples that supports the question to arrive at the correct answer. This paper improves the two-hop Q/A by exposing the model to two-hop predicate paths explicitly. This is done through several tuning based on T5, resulting KNowledge-Integrated T5 (KNIT5):

- Knowledge Integration: given a triple (s,p,o), model is tuned to predict o given s and p.

- Two-hop Knowledge Integration: given two triples (s1, p1, o1) and (o1, p2, o2), model is prefix tuned to predict o2 given s1, p1, o1, p2.

- Either of the two prefix tuning methods below is considered

- Parse-the-Hop: consists of two steps: (i) given input question, model is tuned to parse the question into a two-hop path (s1, p1, o1, p2); (ii) model then predict the answer o2 given (s1, p1, o1, p2).

- MixHop: jointly tune the two steps.

(source: copied from the paper)

The above training paradigm shows to improve substantially the 2-hop capabilities of LMs, but mostly in large LMs. (e.g. T5-XXL).

-

Flexible Grammar-Based Constrained Decoding for Language Models (Geng et al., arxiv 2023)

-

Methods for Measuring, Updating, and Visualizing Factual Beliefs in Language Models (Hase et al., EACL 2023)

-

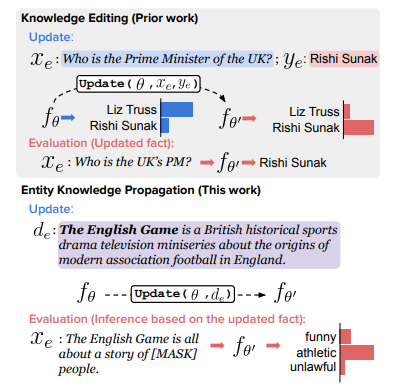

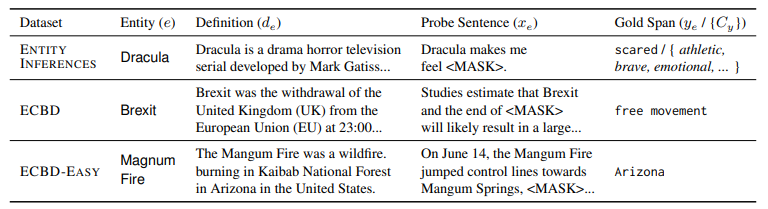

Can LMs Learn New Entities from Descriptions? Challenges in Propagating Injected Knowledge (Onoe et al., ACL 2023)

This work investigates whether LM can add a new entity through entity’s description, propagate this information and performance inference on the new entity.

(source: copied from the paper)

Different from works on injecting facts into LM, where the inference is usually based on the paraphrasing version of injected facts (e.g. upper part of the image above), this work involves higher level of inference complexity, which requires the model learn/propagate new entities from their definitions, and evaluate diverse facts around the new entities. A few examples can be found in the table below:

(source: copied from the paper)

Evaluation metrics for the inference on injected entities:

- Update success: accuracy or perplexity (i.e updated model should have lower perplexity on facts related to new entities)

- Specificity: the entity injection should not impact the existing facts that do not relate to new entities. Or, the perplexity on those facts should not be increased.

Findings: (i) full fine-tuning approach can work effectively on controlled benchmark (LM does not predict an answer for a probe, but instead choose an answer from a set of candidates) , but it comes at the cost of increasing the specificity.; (ii) finetuning for longer does not necessarily propagate the entity’s information into the model; (iii) for more realistic benchmark which require higher level of reasoning/inference, none of model editting techniques improve the update success while keeping specificity stable. Furthermore, author found that such techniques only work when there is lexical overlap between the target inference and the definition of injected entity (e.g. answer span contained in the definition).

-

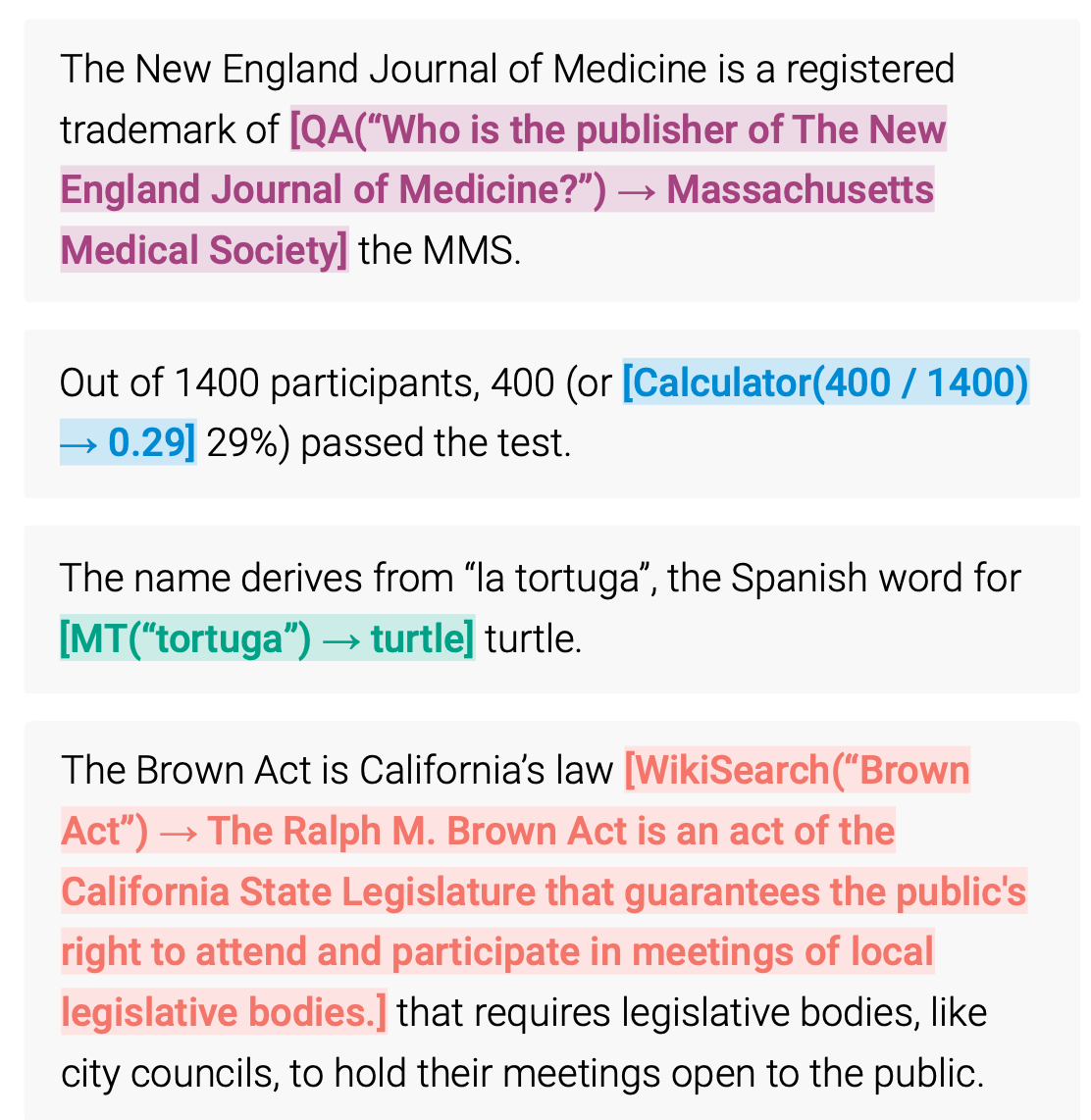

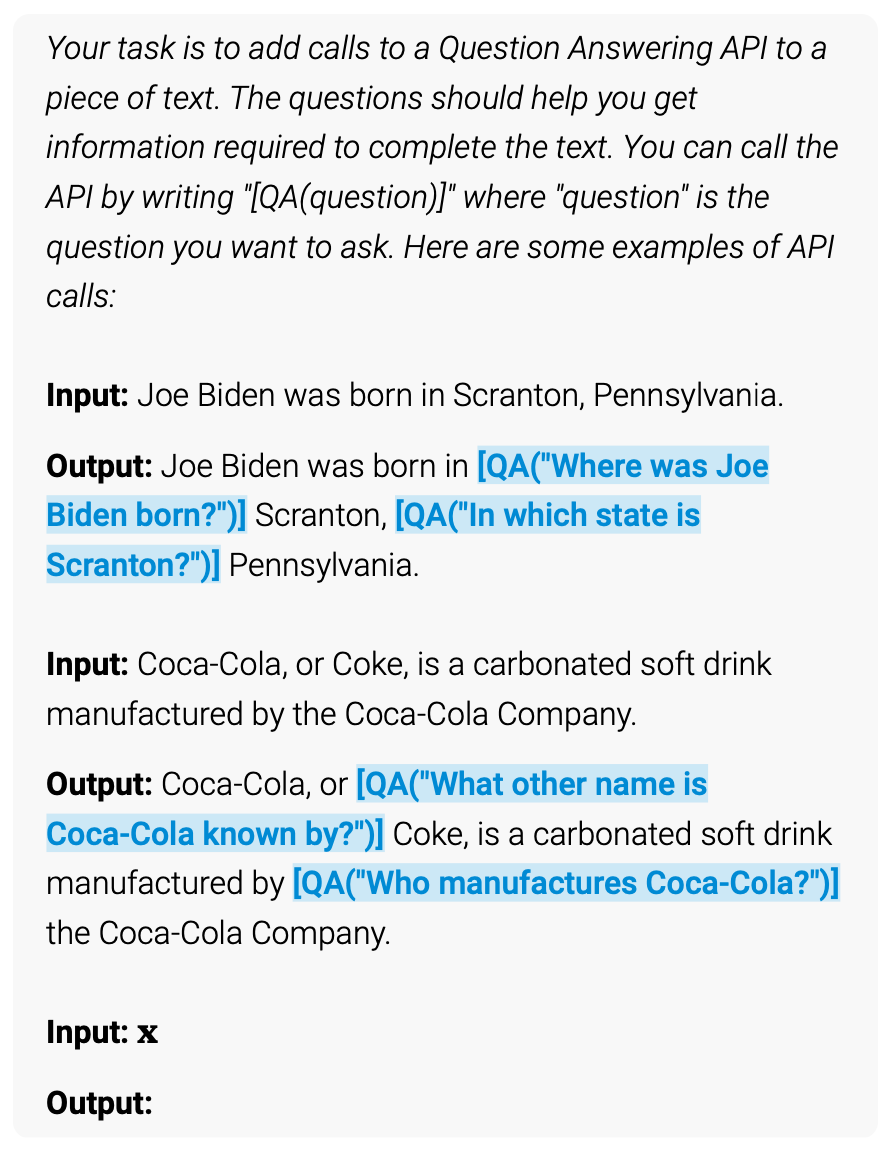

DEMONSTRATE–SEARCH–PREDICT: Composing retrieval and language models for knowledge-intensive NLP (Khattab et al., arxiv 2023)

-

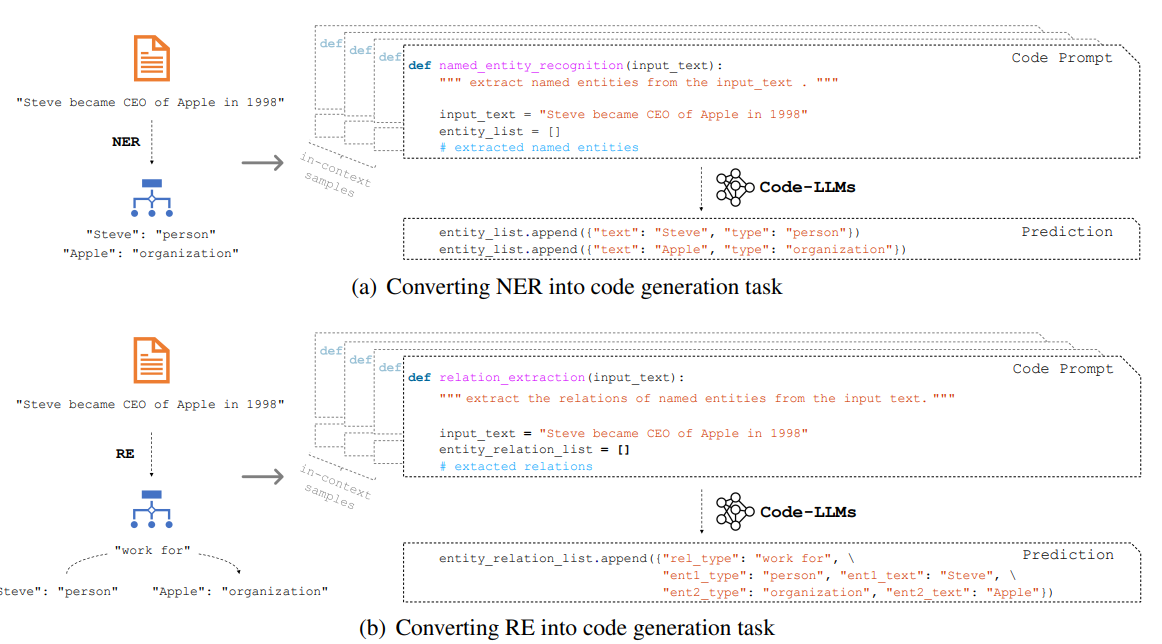

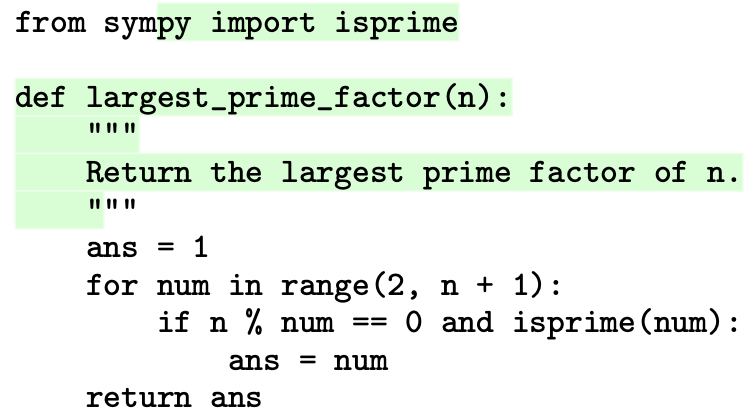

CODEIE: Large Code Generation Models are Better Few-Shot Information Extractors (Li et al., ACL 2023)

Code language model (i.e. model trained on code, among other things) has been discovered that it has better capability to deal with the generation of structured output (e.g. graph, rdf triplet, dictionary…), as code has also structure. Natural-text LM needs to serialize the structured output as plain text, which is very different from what it saw during the pretraining, making the inference difficult.

(source: copied from the paper)

This paper employs a code-LLM (i.e. OpenAI’s Codex) to perform few-shot information extraction (NER and RE). The prompting templates for two tasks are described in the figure above. The results show that:

- Code-style prompt is better than plain-text prompt

- CodeLM has better few-shot performance (even with plain-text prompt) on information extraction tasks than text-LM.

- Code-style prompt with CodeLM yields lower structural error rate. In other words, it can generate the output with correct format.

-

Evaluating Language Models for Knowledge Base Completion (Veseli et al., ESWC 2023)

Previous benchmarks for LM-based Knowledge Base Completion tends to be biased toward popular entities, leading to an overestimate of the completion performance of LM. This paper proposes WD-Know, a new benchmark to address this issue. It relies on Wikidata to extract facts via randomly and equally sampling entities. The new benchmark reveals that the completion accuracy of LM is not equal across relations. While LM achieves high precision and good generalization for language-related and socio-demographic relations (e.g. citizenOf, headquarteredIn), non-socio-demographic relations (e.g. producedBy) may require the fact to be present explicitly (retrieve rather than generalize).

-

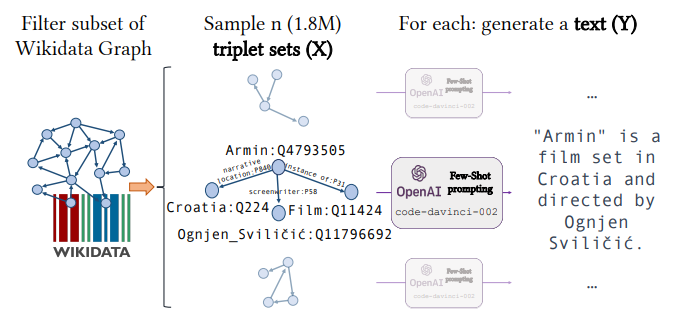

Exploiting Asymmetry for Synthetic Training Data Generation: SynthIE and the Case of Information Extraction (Josifoski et al., arxiv 2023)

Author points out that the lack of a large, balanced, high quality training dataset has been a important obstacle for the success of close Information Extraction (cIE). Indeed, previous datasets exposes several problems: (i) skewness: rare relations/subjects/object appear only a few times. Most models perform poorly on these entities; (ii) noisy: target output does not always contain all the facts conveyed in the input. For these reasons, author proposes to generate a synthetic balanced dataset with the help of LLM. Specifically, LLM is asked to generate text describing a knowledge subgraph fed as input.

(source: copied from the paper)

They then train a FLAN-T5 on this synthetic dataset, yielding SynthIE. Experiments show SynthIE performs much better than GenIE on test synthetic dataset, but much worse than GenIE on REBEL’s test set. They argue REBEL’s test set is a poor approximation of performance.

-

Large Language Model Is Not a Good Few-shot Information Extractor, but a Good Reranker for Hard Samples! (Ma et al., arxiv 2023)

Through an exhaustive evaluation on multiple information extraction tasks (NER, RE, ED), the paper argues that LLM is not an effective few-shot information extractor and still lags behind well-finetuned small LMs, given enough training data. The rationales are:

- Limited number of demonstrations in in-context learning: challenging when dealing with learning problems that involves many labels.

- Author speculates that ICL has difficulty with structured prediction.

In addition, author also found that LLM can work well on samples that seem to be hard for small LMs. This motivates them to propose a hybrid model combining both small LM and LLM. Concretely, samples for which small LM yields small scores are passed to LLM to re-evaluate.

-

Understanding Fine-tuning for Factual Knowledge Extraction from Language Models (Kazemi et al., submitted to JMLR)

This study dives more deeply into the application of using language models to construct a knowledge graph. By investigating the behavior of LMs finetuned for factual knowledge extraction, the author argues that the finetuning process results both positive and negative impacts, depending on the frequency mismatch of entity appearance between the train data and the test data. They relates this issue to the well-known Out-of-distribution generalization in machine learning:

-

Positive impact: if the train and test dataset have similar entity frequency (low mismatch), the fine-tuning yields improvements for knowledge extraction.

-

Negative impact: otherwise (high mismatch), the fine-tuning is no better than zero-shot or few-shot learning due to the appearance of forgetting-related effects: Frequency Shock and Range Shift that may sometimes outweigh positive impact.

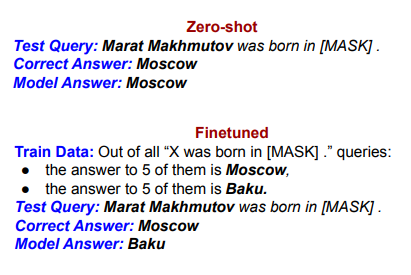

Examples of Frequency Shock are shown below:

(source: copied from the paper)

Even though both “Moscow” and “Baku” are observed an equal number of times (5) during the fine-tuning, “Baku” is less popular then “Moscow” during the pre-training of the LM \(\rightarrow\) the fine-tuned model receives a frequency shock (i.e. “Boku” shift from “unpopular” in pre-training to “as-popular-as” “Moscow” in fine-tuning), making it over-predict “Baku” (rare entity) in the test dataset.

Range Shift: finetuning makes the model tend to predict entities that are seen as answer during the fine-tuning (cold-start problem)

To alleviate the negative impact of finetuning, the paper propose two solutions: (i) ensemble models (fine-tuning + k-shot) as k-show is better than fine-tuning for high mismatch scenario; (ii) mixture training (similar to solution to catastrophic forgetting): jointly fine-tune the model with two objectives: knowledge extraction task and LM objective (e.g. MLM).

-

-

Crawling The Internal Knowledge-Base of Language Models (Cohen et al., TBD)

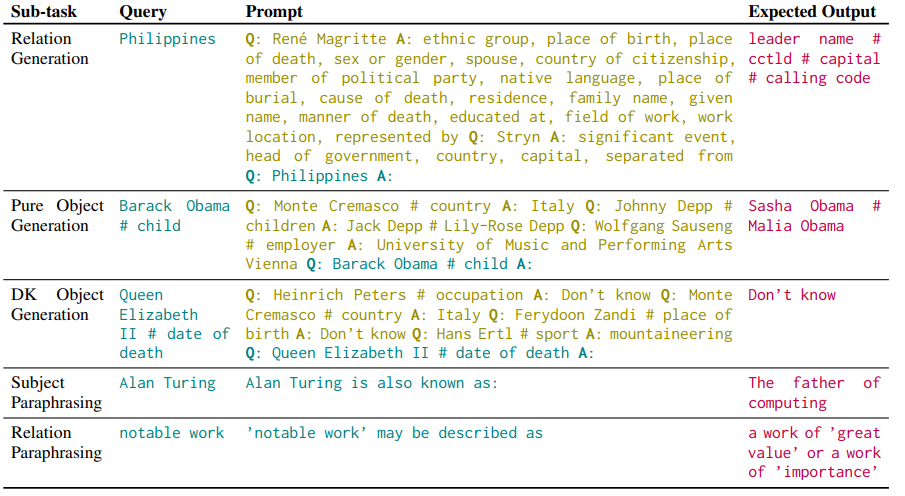

The paper presents LMCRAWL, a pipeline for crawling a subgraph centering around a seed entity, from LM using in-context learning with GPT-3 model.

The crawling processing is decomposed into subtasks:

- Relation Generation: generate a set of relations given subject entity. They leverage Wikidata to generate in-context examples.

- Relation Paraphrasing: generate different surface forms for a relation.

- Subject Paraphrasing: generate different surface forms for an entity.

- Object Generation: given a subject entity and a relation, generate a list of object entities. Only objects that are generated by at least two variants of the relation (via relation paraphrasing) are accepted.

- Learning to say “Don’t Know” instead of giving an erroneous fact: they simply include “don’t know” in-context examples to make the model aware of answering “don’t know” if needed.

Examples of in-context learning are shown below:

(source: copied from the paper)

2022

-

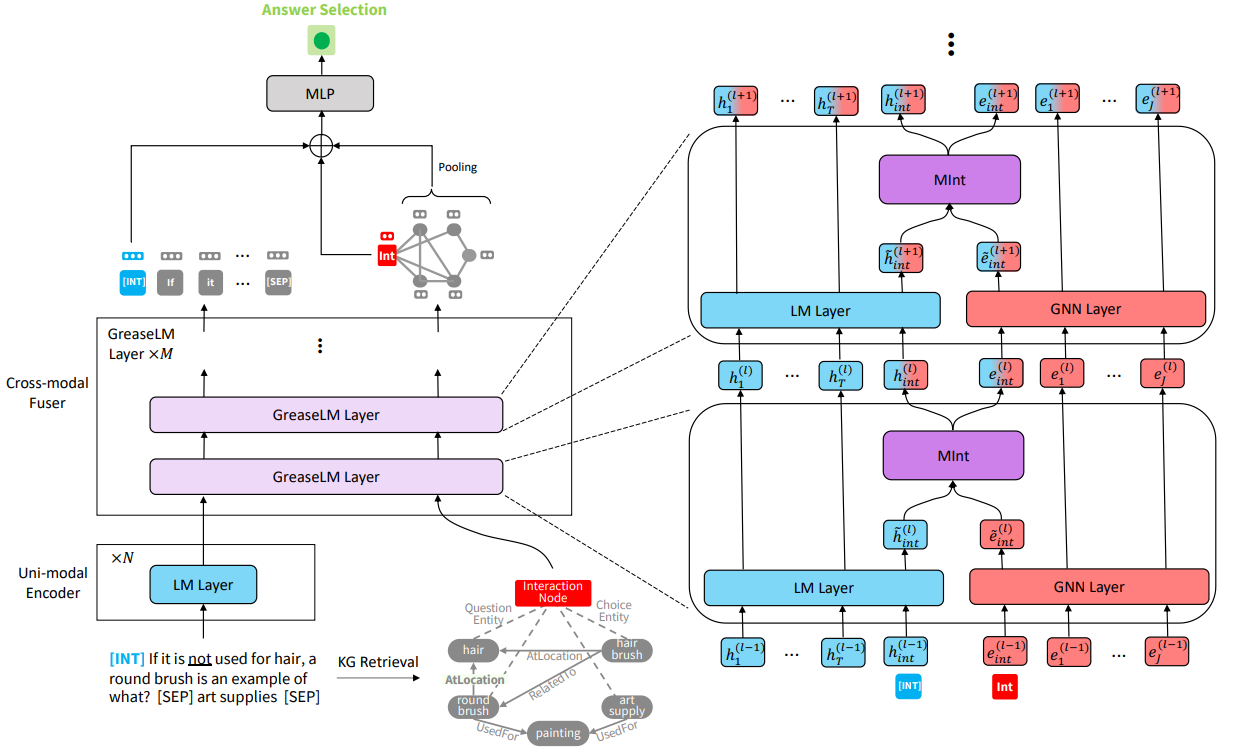

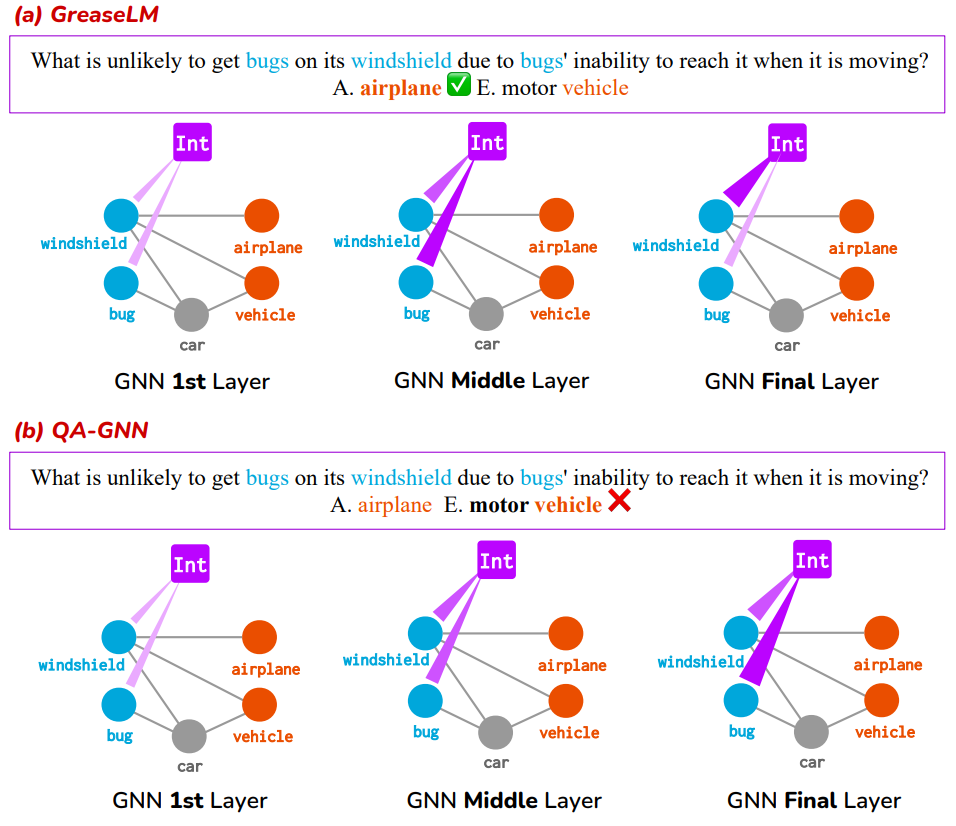

GREASELM: Graph Reasoning Enhanced Language Models for Question Answering (Zhang et al., ICLR 2022)

The paper presents GREASELM, a Graph Reasoning Enhanced LM for improving multiple choice QA. Differing from previous works, GREASELM fuses encoded representations of LM (used to encode QA context) and GNN (used to encode the KG that contains entities appearing in QA context) across multiple network layers. The information propagates from LM to GNN, and vice versa via two proxies: interaction token \(w_{int}\) appended to QA context and interaction node \(e_{int}\) appended to entity graph.

(source: copied from the paper)

GREASELM consists of three components stacked vertically:

- LM representation: an uni-modal encoder of N layers encodes the QA context and the prefix interaction token \(w_{int}\).

- Graph representation and Cross-modal Fuser of M layers:

- An entity linker is employed to extract KG entities from QA context from which a small KG \(\mathcal{G}\) is constructuted.

- The embeddings of entity nodes and proxy interactive node \(e_{int}\) are calculated by graph attention network.

- LM leverages the reasoning skills of GNN by fusing, at every layer, the representations of tokens and nodes through two proxies \(w_{int}\) and \(e_{int}\):

where (\(\hat{\textbf{h}}_{int}^{(l)},\hat{\textbf{e}}_{int}^{(l)}\)) and \((\textbf{h}_{int}^{(l)},\textbf{e}_{int}^{(l)})\) are embeddings of (\(w_{int}\), \(e_{int}\)) before and after fusion. \(Mint\) is a two-layer MLP.

- For multi-choice QA, the score of an answer is computed by another MLP taking in \((\textbf{h}_{int}^{(N+M)},\textbf{e}_{int}^{(M)}, g)\) where \(g\) is attention-weighted embedding of graph entities.

GREASELM demonstrates better performance than previous KG-enhanced LM for CommonsenseQA, OpenbookQA, MedQA-USMLE.

Ablation shows :

- GREASELM’s improvement questions that require complex reasoning: negation, hedging term’s presence.

- Attention visualization makes sense.

(source: copied from the paper)

-

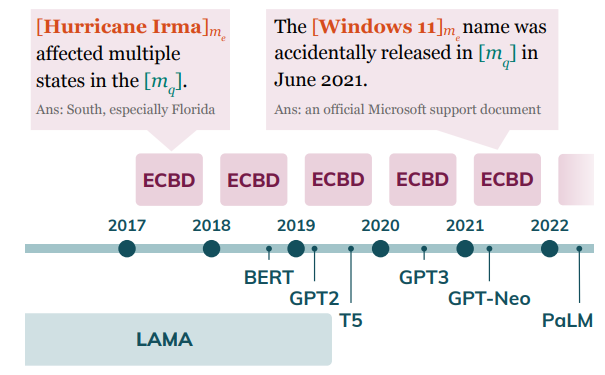

Entity Cloze By Date: What LMs Know About Unseen Entities (Onoe et al., Finding NAACL 2022)

The paper introduces ECBD dataset, containing new entities that are did not exist when the LMs were pretrained, together with cloze sentences in which the entity mentions are found.

(source: copied from the paper)

The masked spans in cloze sentences are chosen that likely relates to the new entities. For each cloze sentence (ORIGINAL), three variants are generated:

- NO ENT: replaces the entity mention span by mention of another entity that is seen during pre-training.

- RANDOM DEFINITION: prepend the definition of a random entity to ORIGINAL.

- DEFINITION: prepend the definition of the gold entity to ORIGINAL.

By measuring the perplexity on 4 categories of cloze sentence, author suggest that injecting additional information (i.e. entity definition) can help the LM guess better (perplexity order: DEFINITION < ORIGINAL~RANDOM DEFINITION < NO ENT) the masked spans related to new entities.

-

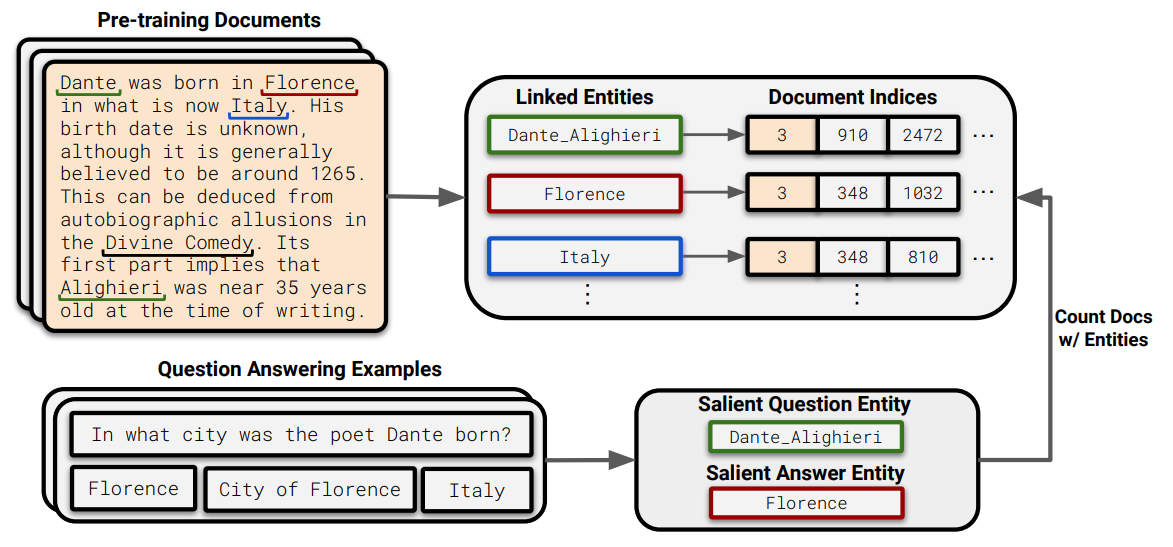

Large Language Models Struggle to Learn Long-Tail Knowledge (Kandpal et al., arxiv 2022)

The paper experimentally shows that the performance of LM on entity-centric knowledge-intensive task (e.g. question-answering) depends strongly in the co-occurrence of {question entity, anwser entity} in the training documents. Specifically, questions related to entities of low frequency result significant low accuracy. They argue this is not due to the questions being “harder”, which causes the drop in the performance, as human performs very well for those questions.

(source: copied from the paper)

-

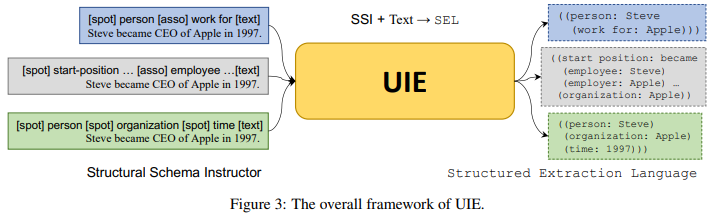

Unified Structure Generation for Universal Information Extraction (Lu et al., ACL 2022)

Universal Information Extraction (UIE) is a unified text-to-structure framework for Information Extraction tasks. It models various IE tasks (NER, EL, RL, etc) within a single T5-based model, allowing different tasks to be jointly learned, to share and collaborate. To this end, UIE introduces two univeral templates for linearizing the heterogeneous input and the heterogeneous output and pre-training scheme to endow the model with common IE abilities (i.e. mapping text to structure, decoding structure).

In more details:

- SSI (Structural Schema Instructor) template to represent the heterogeneous input: e.g. \(\textsf{[spot] person [asso] work for [text] Steve became CEO of Apple in 1997}\) where special tokens \(\textsf{[spot]}\) and \(\textsf{[asso]}\) indicate what to extract in \(\textsf{[text]}\) (\(\textsf{[spot]}\): person entity, \(\textsf{[asso]}\): its attribute).

- SEL (Structured Extraction Language) template to represent the heterogeneous output such as \(\textsf{((entity: (attribute: )))}\): e.g. \(\textsf{((person: Steve (work for: Apple)))}\) for the above input.

- Pre-training paradigm: UIE is jointly trained with three objectives: (1) text-to-structure with Wikipedia-Wikidata aligned (text, KB triplets) pairs. (2) UIE decoder pretraining to autoregressively predict components (predicate, object) in KB triplets. (3) T5’s training objective: span corruption based MLM.

-

Rejection Machanism: adding NULL to the training data to help the model learn to reject misleading generation.

Example Encoder: <spot> person ... <spot> facility <asso> ... <text> Steve became CEO of Apple in 1997. Decoder: ((person: Steve (work for: Apple)) (facility: [NULL]) ...

(source: copied from the paper)

-

GenIE: Generative Information Extraction (Josifoski et al., NAACL 2022)

Close Information Extraction (cIE) typically aims at extracting an exhaustive set of relational triplets \((subject, relation, object)\) from given text where \(subject/object\) entity and \(relation\) are constrained to come from a predefined knowledge base. Traditional cIE pipeline encompasses multiple independent sub-tasks (NER, NED, RE) which suffers from the error accumulation. GenIE is an end-to-end autoregressive cIE system that casts the triplet extraction as text-2text problem in which the decoder generates entities and relations token-by-token in an autoregressive fashion. They introduce special tokens <sub>, <rel>, <obj>, <end_of_triplet> to linearize the generated output. To assure that generated tokens refer to valid entity and relation, GenIE employs constrained beam search to guide the decoding following prefix tries built on the entity set and the relation set of the knowledge base. This makes the beam search effective for large million of entities.

Example Encoder: John Smith acts in the movie Wichia Decoder: <sub> Wichia (1995 film) <rel> cast member <obj> John Smith (actor) <end_of_triple> <sub> Wichia (1995 film) <rel> instance of <obj> film <end_of_triple>GenIE enforces the order of generated triplets in the way that triples for which the subject entity appears earlier in the text will be generated first.

GenIE can be extended to the generation of literal object \(\rightarrow\) similar to open Information Extraction where the object does not need to be aligned with a KB.

-

EIDER: Empowering Document-level Relation Extraction with Efficient Evidence Extraction and Inference-stage Fusion (Xie et al., ACL Findings 2022)

EIDER: Extracted Evidence Empowered Relation Extraction

(source: copied from the paper)

Typical document-level relation extraction models rely on the whole document to infer the relation of an entity pair in the document. On the one hand, a minimal set of sentences (i.e. evidences) in the documents is enough for human to annotate the relation, taking the whole document as input may add noise and ambiguity to the model. On the other hand, there is no way to extract such minimal set perfectly, leading to missing important information. EIDER alleviates both aspect by introducing:

- Joint training of relation extraction end evidence sentence extraction: a base encoder is employed to learn the representation of the relation from the counterparts of the head entity, tail entity and the whole document \(p(r \mid e_h, e_t, c_{h,t})\), as well as to learn the representation of each evidence sentence \(s_n\) given the head and tail entity \(p (s_n \mid e_h, e_t)\). For the training, evidence sentences for each entity pair in a document can be either manually provided, or extracted using simple heuristics (e.g. a sentence containing both head and tail entities is considered as an evidence for this entity pair).

- Fusion of evidence in Inference: the score of each candidate relation is given by two inferences: one with the prediction from the whole documents, one with the prediction from the set of extracted evidence sentences (a subset of original document). \s

-

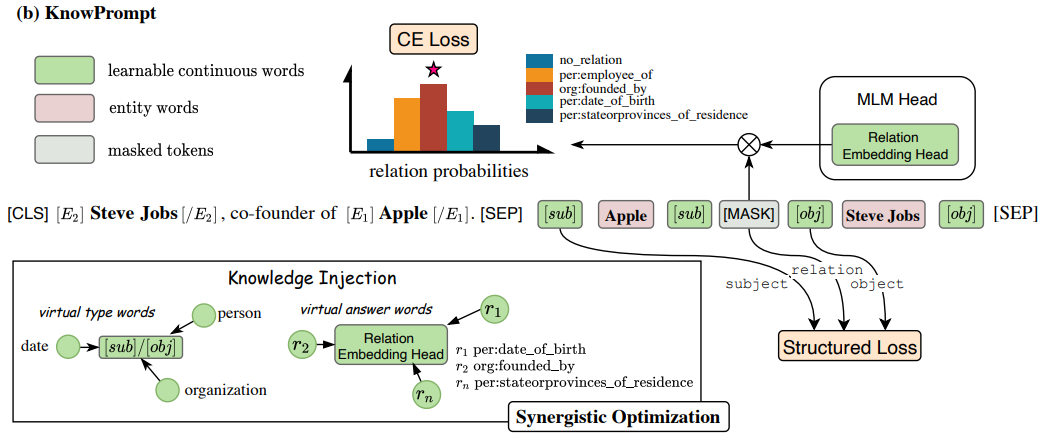

KnowPrompt: Knowledge-aware Prompt-tuning with Synergistic Optimization for Relation Extraction (Chen et al., The WebConf 2022)

KnowPrompt: prompting with knowledge constraint

(source: copied from the paper)

KnowPrompt relieves the cumbersome prompt engineering by representing the prompt template and prompt verbalizer by learnable virtual words. Specifically, given a prompt: \(\textsf{[CLS] It solds [E1] ALICO [/E1] to [E2] MetLife Inc [/E2] for \$162 billion. [SEP] [sub] ALICO [sub] [MASK] [obj] Metlife Inc [obj]. [SEP] }\) where the first sentence is the context in which foreknow sentinel tokens \(\textsf{[E1], [E2]}\) indicates entities whose relation will be discovered in the second sentence. Three tokens \(\textsf{[sub], [MASK], [obj]}\) are considered as virtual words representing the subject entity type, the relation, and the object entity type respectively. The possible relation \(r\) between \(\textsf{E1}\) and \(\textsf{E2}\) is computed from the probability distribution at \(\textsf{[MASK]}\) token.

To guide \(\textsf{[sub], [obj]}\) to represent meaningfully the associated entity \(\textsf{E1, E2}\) as well as to encode the structural constraint between them and the relation, KnowPrompt:

- Instead of random initialization, the embeddings of \(\textsf{[sub], [MASK], [obj]}\) are initialized with prior distribution (calculated by frequency statistics) of entity type’s word-embedding and relation’s word embedding.

- Incorporate structural knowledge constraint: apart from LM loss, inspired by knowledge graph embedding, KnowPrompt interprets \(\textsf{[MASK]}\) as a translation from \(\textsf{[sub]}\) to \(\textsf{[obj]}\) (similar to TransE), leading to the minimization of the Euclidean distance in the embedding space: \(d([sub], [obj]) = \mid \mid [sub] + [MASK] - [obj] \mid \mid_2\)

-

Rewire-then-Probe: A Contrastive Recipe for Probing Biomedical Knowledge of Pre-trained Language Models (Meng et al., ACL 2022)

Contrastive-Probe for Knowledge probing from LM.

Knowledge probing approaches based on mask prediction or text generation have two typical drawbacks:

-

Multi-token span prediction: the mask prediction approaches use the MLM head to fill in a single mask token in a cloze-style query \(\rightarrow\) if an answer entity names that contain multi-token span, the query needs to be padded with the same amount of [MASK] token.

-

The answer may not be a valid identifier of an entity: the mask prediction or text generation approaches rely on the vocabulary to generate the answer in an unconstrained way \(\rightarrow\) the generated texts may not exist in the answer space. Furthermore, different LMs can have different vocabularies, leading to the vocabulary bias.

The paper introduces Contrastive-Probe to address two above issues by avoiding using the LM head for mask prediction or text generation. Similarly to sentence embedding approaches, Contrastive-Probe employs the LM to encode the prompt query \(q\)(e.g. “Elvitegravir may prevent [Mask]”, [Mask] can represent multiple tokens) into the embedding \(e_q\) and encode each answer (e.g. “Epistaxis”) in the complete answer space into another embeddings \(e^i_s, i=1..N\) where \(N\) is the size of answer space. The K-nearest neighbors \(e^k_s, k=1..K\) of \(e_q\) in the embedding space are considered as the answer of \(q\). Self-supervised contrastive learning is used to rewire the pretrained LM to this answer-retrieval task. Specifically, with infoNCE objective loss, the PLM is fine-tuned on {query, answer} pairs in order for the {query, correct answer} pairs (positive samples) stay close to each other and {query, other answer in the same batch} pairs (negative samples) are pulled far apart.

Testing on bio domain, Contrastive-Probe achieved several following results:

- Contrastive-Probe outperforms other probing baselines (mask prediction, text generation) ) regardless of the underlying PLM on MedLAMA benchmark for Bio domain.

- It is effective at predict long answer (aka. multi-token span)

- In phase with previous observation, no configuration fits all relations. Different relation require different underlying LM, different depth of tuning layer for the best performance.

- It is pretty stable in performance where training with different dataset results small deviation and similar trend.

-

-

Do Pre-trained Models Benefit Knowledge Graph Completion? A Reliable Evaluation and a Reasonable Approach (Lv et al., ACL-Findings 2022)

The paper demonstrates that PLM-based KGC models are still left quite behind the SOTA KGC models (e.g. KGE models) because the evaluation benchmark is conducted under the closed-world assumption (CWA) where any knowledge that does not exist in a given KG is said to be incorrect. Indeed, PLM is known to implicitly contain more open knowledge unseen in a KG. By manually verify the veracity of Top-1 prediction of KGC models, they show that PLM-based models outperforms SOTA KGE-based models for the link prediction and the triple classification tasks.

Likewise many other models, this work also make use of prompting method to elicit the knowledge from PLM. A hard prompting template is manually designed for a relation to represent the semantics of the associated triples. For example, relation <X, member of sport teams, Y> has the template X plays for Y. To further improve the expressivity of triple prompts, two other kinds of prompts are added into the triple prompt:

- Soft prompts (i.e. learnable sentinel tokens [SP]): play as separators to signal the position of template components and entity labels in the triple prompt. For example, the prompt X plays for Y after adding soft prompts becomes [SP1] X [SP2] [SP3] plays for [SP4] [SP5] Y [SP6]. Each relation has its own set of soft prompts \([SP]_i, i=1..6\) and they are all learnable via triple classification objective.

- Support prompts: entity definition and entity attribute are useful information that can help the KGC. Therefore, they are concatenated to the triple prompt through two templates: “[Entity]: [Entity_Definition]” and “The [Attribute] of [Entity] is [Value]”. As an entity has many attributes, only few attributes are randomly selected. The results reveal that the entity definition provides more gain than entity attributes.

Additionally, their analysis conveys two messages: (i) by counting number of sentences in the training that contain both the head and the tail of a triple, it indicates that PLM-based KGC still outperforms KGE-based KGC on the triples with zero co-occurrence of {head, tail} in the training set \(\rightarrow\) they argue PLMs, apart from seeing many facts in the massive text, have the ability to reason the knowledge. (i) PLM-based KGC models are less sensitive to the size of training dataset where reducing the training data size decreases slightly the prediction accuracy.

-

SimKGC: Simple Contrastive Knowledge Graph Completion with Pre-trained Language Models (Wang et al. ACL 2022)

SimKGC: Promptless method for KGC based on sentence embedding

To predict an entity \(e_i \in KG \; \mathcal{E}\) for a triple \(<h, r, ?>\), SimKGC employs a PLM-based bi-encoder architecture where two encoders do not share parameters. One encoder computes the relation-aware embedding \(e_{hr}\) for the head entity \(h\) from the concatenation of the descriptions of the head entity and the relation: “[header_description] [SEP] [relation_description]”. Another encoder is leveraged to compute the embedding of the description of the candidate tail entity \(e_t\). Candidate tail entities \(e^i_t\) are ranked according to the cosine similarity between its embedding and the relation-aware embedding of the head entity \(e_{hr}\). The bi-encoder is trained to learn useful representation for head entity and tail entity in the triple using contrastive learning.

The paper argues that the reason why previous contrastive learning-based models are lag behind SOTA KGE-based models highly involves the ineffectiveness of training setting for contrastive learning where they use small negative sample size (\(\approx\) 1..5 due to computational complexity) and the margin loss. Indeed, by augmenting the number of negative sample per positive sample (e.g. 256) and changing the margin loss to InfoNCE loss, they obtain much better performance and outperform KGE-based models.

For further improvement, in addition to in-batch negative, SimKGC also combine two other strategies for generating negative samples:

- Pre-batch Negatives: sample batches at training step \(t-1\), \(t-2\)… can be considered as negative samples for current training batch at step \(t\).

- Self-Negatives: triple \(<h, r, h>\) (tail entity is predicted as head entity) is seen as a hard negative sample for the triple \(<h, r, ?>\) \(\rightarrow\) this makes the model rely less on the spurious text matching/overlapping to make the prediction.

Lastly, the work also stresses that predicting one-to-many, many-to-one, many-to-many relations is more difficult.

-

Task-specific Pre-training and Prompt Decomposition for Knowledge Graph Population with Language Models (Li et al., LM-KBC@ISWC 2022 Challenge)

This work continues to pre-train BERT with task-specific data to make it familiar with the task. How ? triples <sub, rel, obj> are verbalized into a sentence using a prompt template of rel. As the task is object prediction, the object or surround words in the sentence are masked and the LM is asked to predict them. Large dataset is necessary for pre-training, hence, they leverage Wikidata for data augmentation where they generate KG triples that have same relations as provided training relations). However, they discover later that the accuracy does not clearly relate to data size but the property of relation (see below).

- Prompt generation: they curate a set of prompts for a relation both in manual and automatic way. In manual way, they explicitly append the type of the subject into the prompt, such as “The musician [SUBJ] plays [OBJ]” for relation “PersonInstrument”. In automatic way, they employ two methods from How Can We Know What Language Models Know?. However, in contrast to How Can We Know What Language Models Know?, this paper shows that an ensemble of automatically-generated prompts is not better than a single manual-curated one.

- Prompt decomposition: a relation can have diverse domain and diverse range. For example, considering the relation “StateSharesBorderState”, its domain can include “Andalusia”-is a autonomous community or “Hebei” - a province. To better distinguish the type of the subject and probe more relevant knowledge from LM, two prompts are performed:

- ask for subject type: e.g. e “[SUBJ], as a place, is a [TYPE]”.

- inject the subject type into the prompt of the relation: e.g. “[SUBJ] [TYPE] shares border with [MASK] [TYPE]”.

2021

-

GENRE: Autoregressive Entity Retrieval (De Cao et al., ICLR 2021).

Very interesting entity retriever that casts the entity linking problem as a text-to-text problem and employs a seq2seq model (i.e. BART) to address it.

Example:

Encoder: In 1503, Leonardo began painting the Mona Lisa Decoder: In 1503, [Leonardo](Leonardo da Vinci) began painting the [Mona Lisa](Mona Lisa) where [X](Y) : X is the mention, and Y is the entity label (aka. entity identifier) that represents X.Importantly, they perform the inference with constrained beam search to force the decoder to generate the valid entity identifier. Specifically, at a decoding step \(t\), the generation of the next token \(x_t\) is conditioned on previous ones \(x_1,..., x_{t-1}\) such that \(x_1,..., x_{t-1}, x_{t}\) is a valid n-gram of an entity identifier.

-

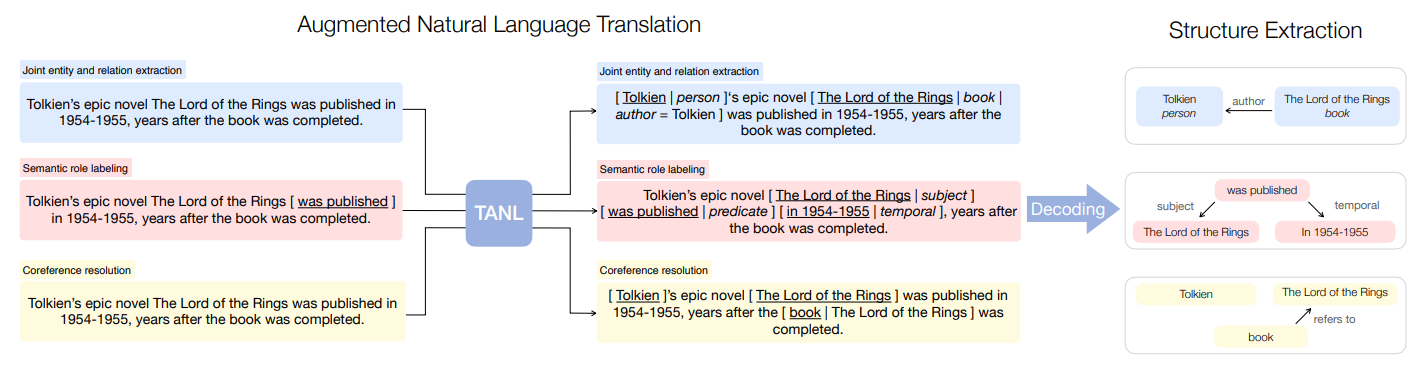

Structured Prediction as Translation Between Augmented Natural Languages (Paolini et al., ICLR 2021)

Many knowledge extraction tasks such as NER, EL, Relation extraction, etc can be seen as structured prediction tasks where the output space consists of structured objects such as entities, relations.

Translation between Augmented Natural Languages (TANL) frames multiple prediction tasks as text-2-text problems and employs an unified architecture (e.g. BART, T5, etc) to solve all those tasks without task-specific designs. To this end, they propose informative templates (called augmented language) to encode structured input and decode output text into structured objects.

(source: copied from the paper)

One remarkable feature of TANL’s encode scheme is its ability to represent nested entities and multiple relations, as illustrated in example below: